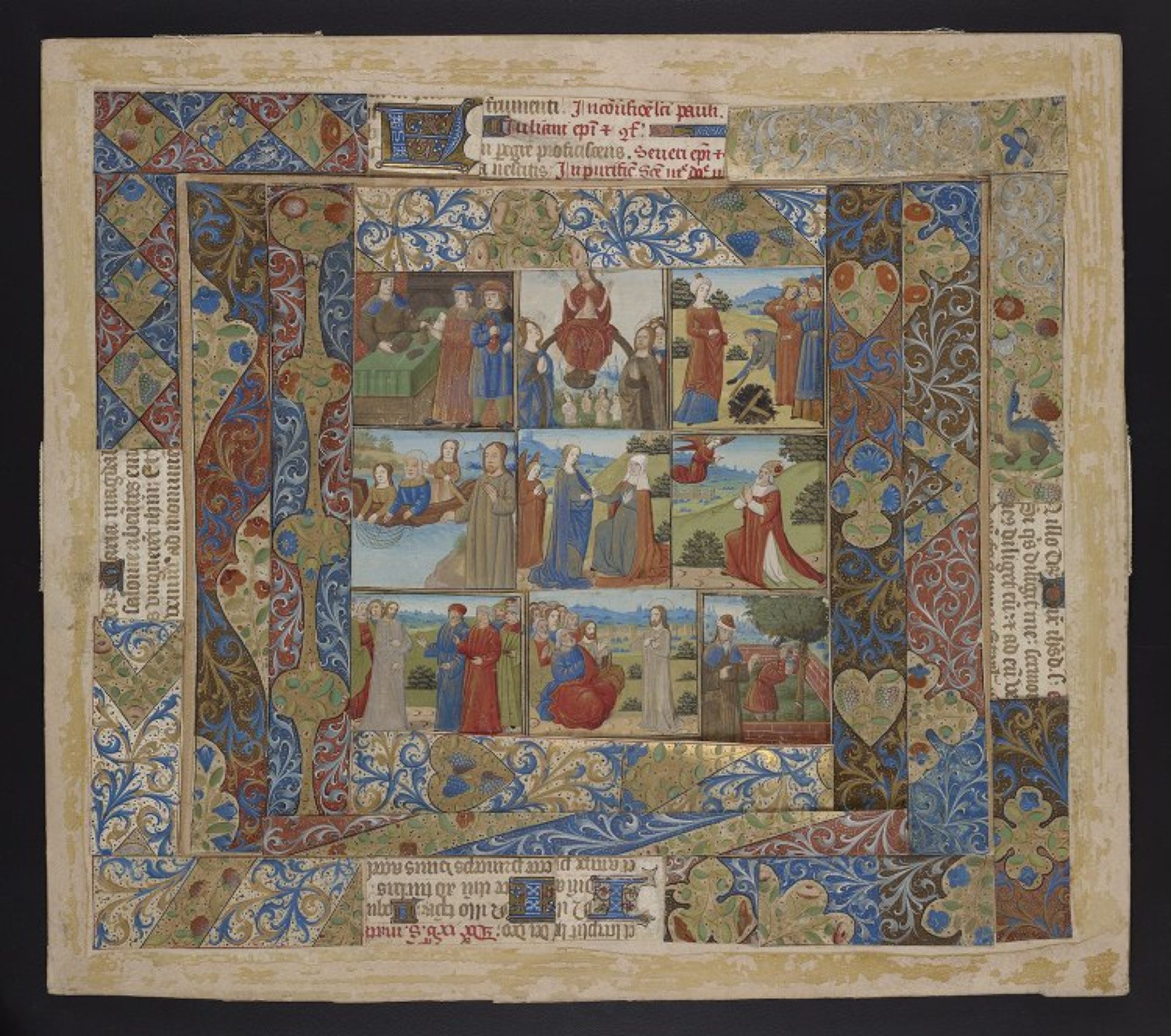

Originally presented at the 14th Annual Schoenberg Symposium on Manuscript Studies in the Digital Age, November 17, 2021

Thank you for that kind and generous introduction and thanks to Lynn for inviting me to present this talk today. Thank you to all of you this afternoon, or this evening for those of you in Europe, for sticking around for my talk tonight on manuscript loss in digital contexts.

I want to do a couple of things with his paper and I’m not entirely sure that they go together so please bear with me. The first thing that I want to do is to look back over some specific things that have been said in the past about loss and manuscript digitization specifically. There’s quite a long history of both theorists and practitioners giving lectures and responding to the topic what we lose when we digitize a manuscript – how much digitized manuscripts lack in comparison with “the real thing” and all of the reasons why digitized manuscripts aren’t as good as the real thing because of these losses. I want to address those complaints and to respond to them with examples of work that that we’ve been doing at Penn that I think answers some of these issues. The second thing that I want to do is to showcase the Lightning Talks. Last month we put out a call for five minute presentations, for anybody who wanted to submit a paper on the issue of loss specifically in digital work and digitization – this was this was the ask that we put out:

“The theme of this year’s symposium is Loss and we are particularly interested in talks that focus on digital aspects of loss in manuscript studies.”

From the call for Lightning Talk proposals, Schoenberg Symposium 2021

I was pleasantly surprised by the submissions, which didn’t cover old ground and in some cases respond to some concerns that have been expressed about digitized manuscripts in the past.

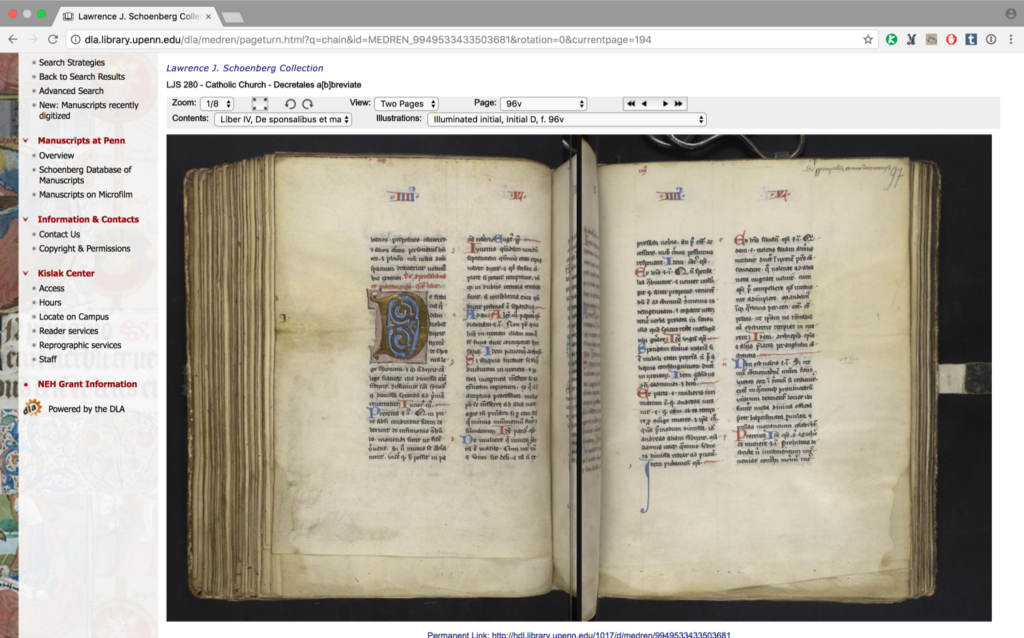

In June 2013 ASG Edwards published a short essay called “Back to the real” in the Times literary supplement.[1] I cannot overstate the affect that this piece had on those of us who were creating digitized manuscripts. When this piece came out I’d been at Penn for about three months, having just started my position in April 2013, and although Penn had been digitizing its manuscripts for many years and there was an interface, Penn In Hand, which is still available, this was before OPenn, well before BiblioPhilly, before VisColl. The first version of Parker on the Web, which Edwards names in his piece, had been released on 1 October 2009, but it was behind a very high paywall, which was only lifted when Parker on the Web 2.0 was released in 2018. 2013 was also about a year after the Walters Art Museum had published The Digital Walters, and released that data under an open access license, and I came to Penn knowing that we wanted to recreate the Digital Walters here – the project that would become OPenn – so at that point in time we were thinking about logistics and technical details, how we could take the existing data Penn had and turn it into an open access collection explicitly for download and reuse as opposed to something that was accessed through an interface.

Mid 2013 was also when a lot of libraries were really starting to ramp up full-manuscript and full-collection digitization – digitization at scale, full books and full collections, as opposed to focusing only on the most precious books, or digitizing only sections of books. I also discovered that this was two years after the publication of “SharedCanvas: A Collaborative Model for Medieval Manuscript Layout Dissemination,” a little article published in the journal Digital Libraries in April 2011 by Robert Sanderson, Ben Albritton, and others, which is notable because it is what would eventually become the backbone of the International Image Interoperability Framework, or IIIF, which I will mention again.

Edwards’s piece has been cited and quoted many times over the eight years since it was published and it for good reason. Edwards doesn’t pull any punches, he says exactly what he’s thinking about with regards to digitized manuscripts and honestly as somebody who was in the thick of things in summer 2013 this so this came as a little bit of a bomb in the middle of that. Since this is such a such primary piece I want to look at his concerns and see how they hold up eight years later.

“The convenience of ready accessibility is beyond dispute, and one can see that there may be circumstances in which scholars do have a need for some sort of surrogate, whether of a complete manuscript or of selected bits. But the downsides are in fact many. One of the obvious limits of the virtual world is the size of the computer screen; it is often difficult for viewers to take in the scale of the object being presented.”

A. S. G. Edwards, “Back to the real”

The issue of interpreting the physical size of manuscripts in digital images is an obvious one and it’s one that I talk about a lot when I talk to classes and school groups. Edwards is correct – it is difficult to tell the size of an object when it’s presented in an in an online interface and there are a few different reasons for that. So I’m going to take a look at two manuscripts in comparison with the thinking that comparative analysis might be helpful.

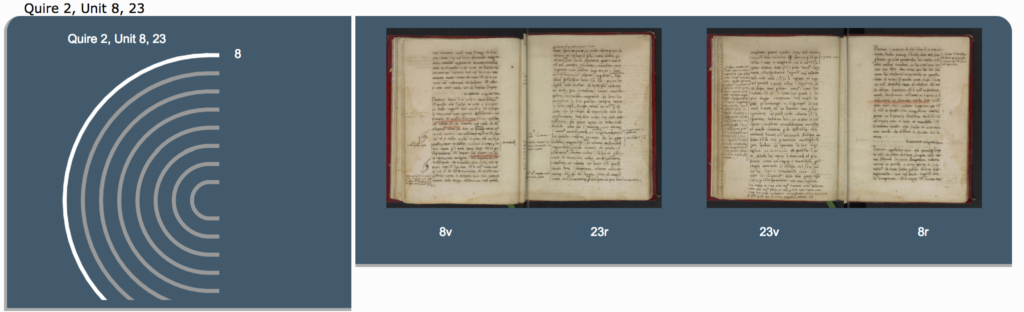

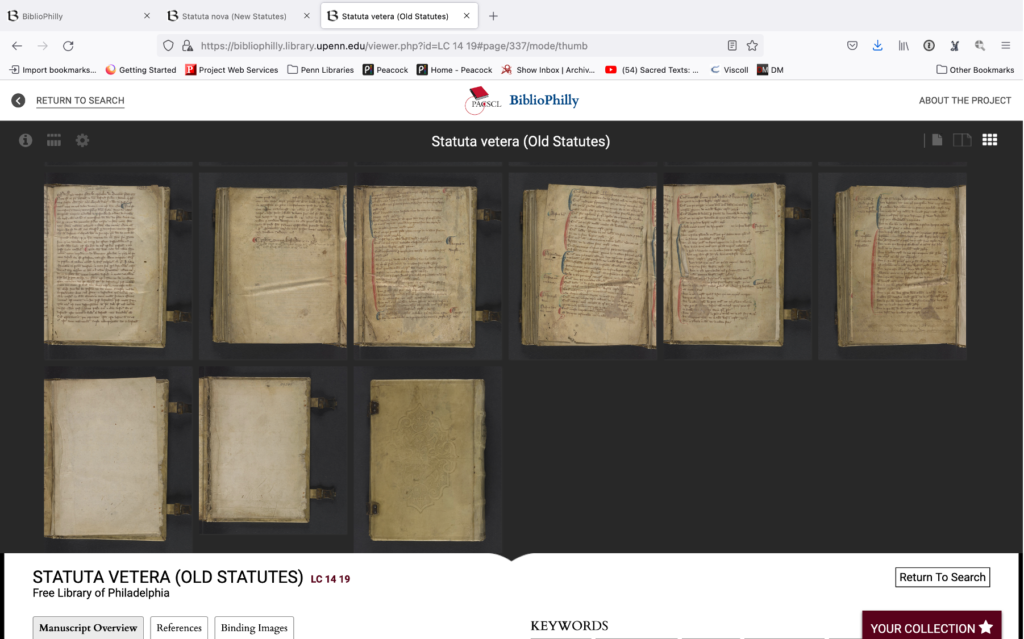

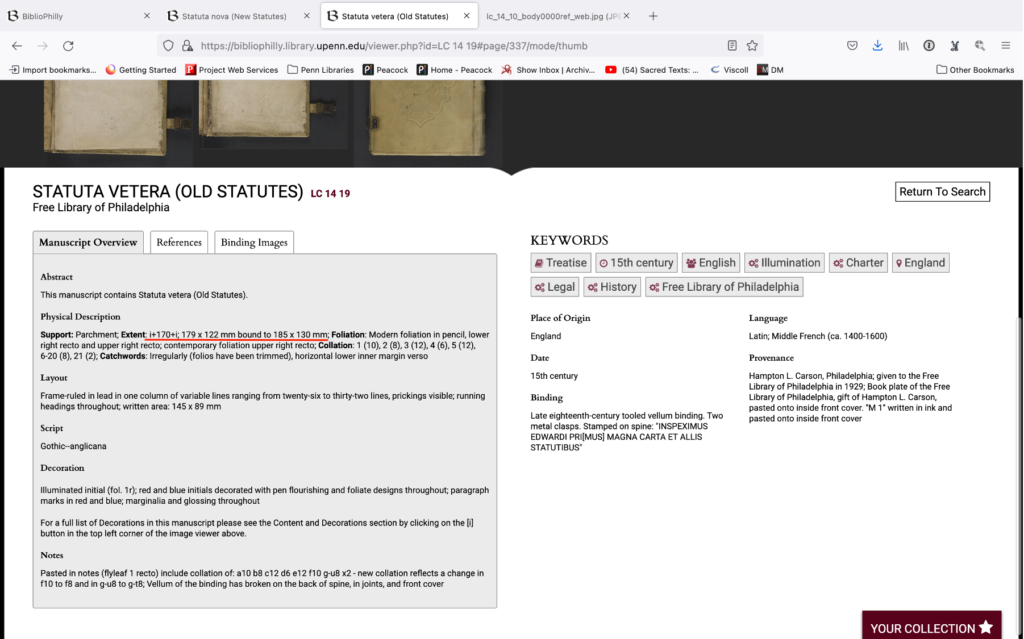

Both of these manuscripts are from the Free Library of Philadelphia, and they were digitized as part of the Biblioteca Philadelphiensis project and I’m showing them here in the BiblioPhilly interface, which was created for this project. They’re both 15th century manuscripts from England. FLP LC 14 19 is a copy of the old statutes, the statutes of England beginning with the Magna Carta, a document first issued in 1215 by King John (ruled 1199-1216), and FLP LC 14 10 is a copy of the new statutes, English legal statutes beginning with the reign of Edward III (ruled 1327-1377).

FLP LC 14 10 (New Statutes) is pictured on the left and FLP LC 14 19 (Old Statutes) is on the right. I present them to you like this to give you a sense of how these two manuscripts look on the surface, and I’m going to point out some things that I notice as we go back-and-forth that gives me clues to their relative sizes.

The old statutes and the new statutes, both of these manuscripts have clasps, in the case of the old statutes manuscript, or remnants of clasps in the case of the new statutes. I have a sense of how large the clasps are in comparison with the rest of the book so the clasps look bigger to me on the old statutes, they take up more space. The decoration also looks bigger on the old statutes cover. Both of these covers have decoration embossed on the front and the new statutes book has a lot more of them and they’re thin. Which implies to me that the new statute book is bigger than the old one.

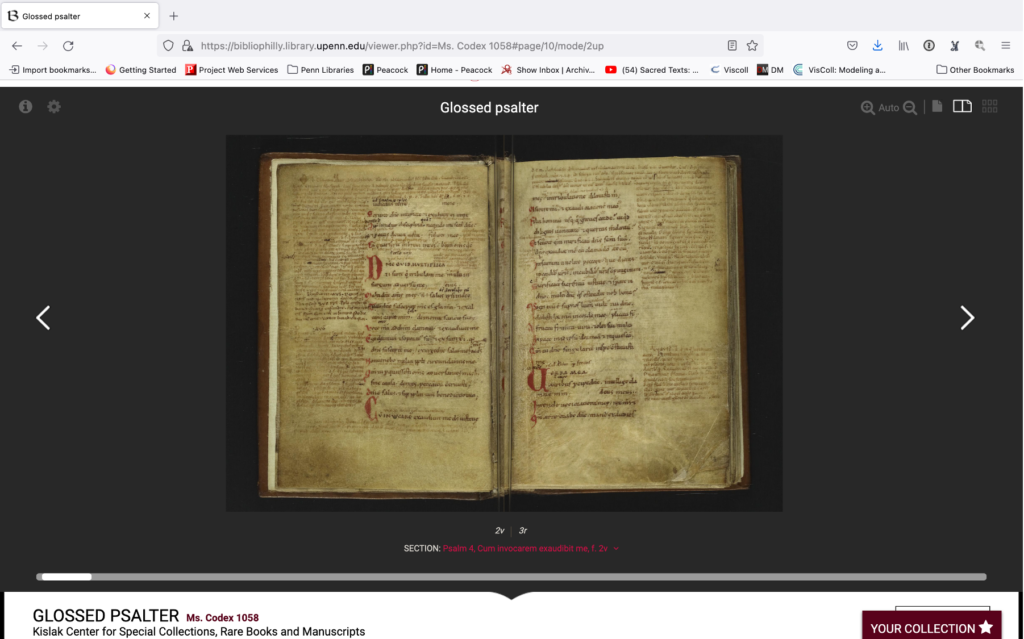

Now let’s look inside – again, FLP LC 14 10 (New Statutes) is pictured on the left and FLP LC 14 19 (Old Statutes) is on the right. Immediately I notice that the new statutes manuscript has more lines and there appear to be more characters per line and the writing looks smaller than it does in the old statutes manuscript. So again, what this implies to me is that the new statutes manuscript is bigger because you can write more in it. Now I’ve seen enough manuscripts to know that this can be misleading. There are many very small manuscripts that contain tiny tiny writing – like Ms. Codex 1058 from Penn’s collection.

This is a glossed Psalter, and back in 2013 before I arrived at Penn I spent a lot of time looking at this manuscript online. The first time that I saw it in person I was absolutely floored because it is so much smaller than the writing implied to me – for reference, the codex is 40 mm, or 1.5 inches, shorter than the old statutes manuscript. It’s small, and by including it here I’m aware that I’m helping to prove Edward’s point – although comparing the two statutes manuscripts is helpful in coming up with size cues, it’s still really difficult to tell generally, at least in this interface.

“It is also difficult to discern distinctions between materials such as parchment and paper, and between different textures of ink.”

A. S. G. Edwards, “Back to the real”

Let’s turn back to the two statutes manuscripts again. We’ll look at the support – zoomed in to 100% so we’re very very close to the material.

If you know what parchment looks like and if you know what paper looks like I think that it’s clear that both of these manuscripts are written on parchment. One of these is darker than the other one, that could be because of the type of animal the parchment comes from, or variance between hair and flesh side, or it could be how it was produced. Also some of the things that you’ll look for in parchment like hair follicles are not immediately clear at least in these examples.

I haven’t yet mentioned training and the knowledge that you bring with you when you come to a digitized manuscript but I think that’s really important. If you are familiar with the statutes manuscripts, if you’ve seen several of them you know that the new statutes are much longer than the old statutes and so new statutes manuscripts are bigger and old statutes manuscripts are smaller, and that’s just something that you know. You probably didn’t know that but I knew that and that knowledge is reflected in what we’ve already looked at for those manuscripts.

It’s the same for parchment and paper. if you’ve been trained and you know what parchment looks like and you know what paper looks like then you’re going to be able, most of the time, to tell the difference between them in digital images.

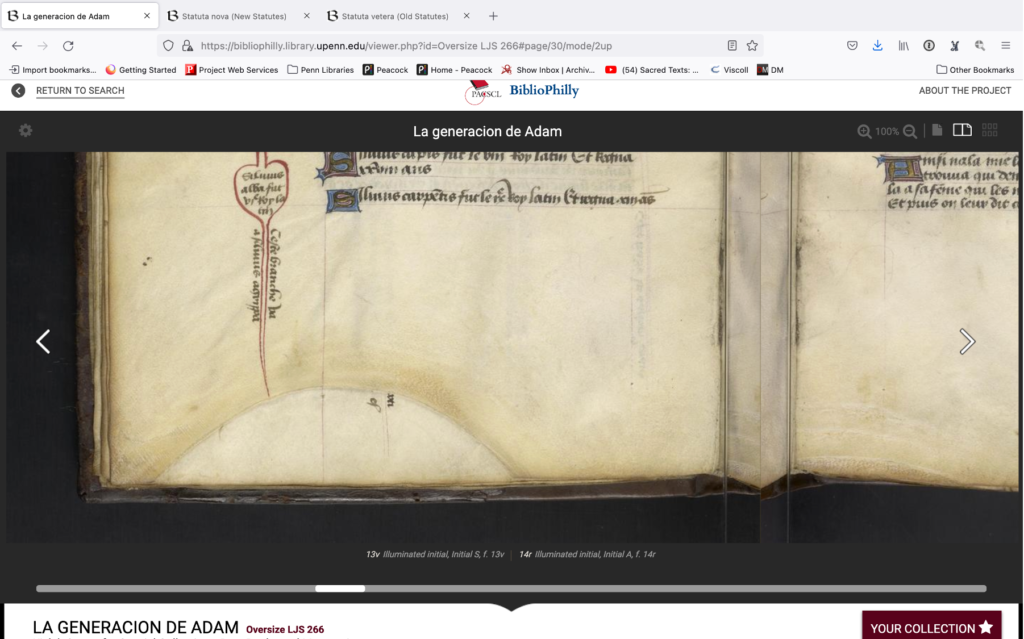

This next example is from another manuscript, LJS 266 from the Schoenberg collection, and this is something that’s very typical in parchment manuscripts. That rounded area is an armpit of the animal, and you can also see some hair follicles around there. So this is very clearly a parchment manuscript and not a paper manuscript.

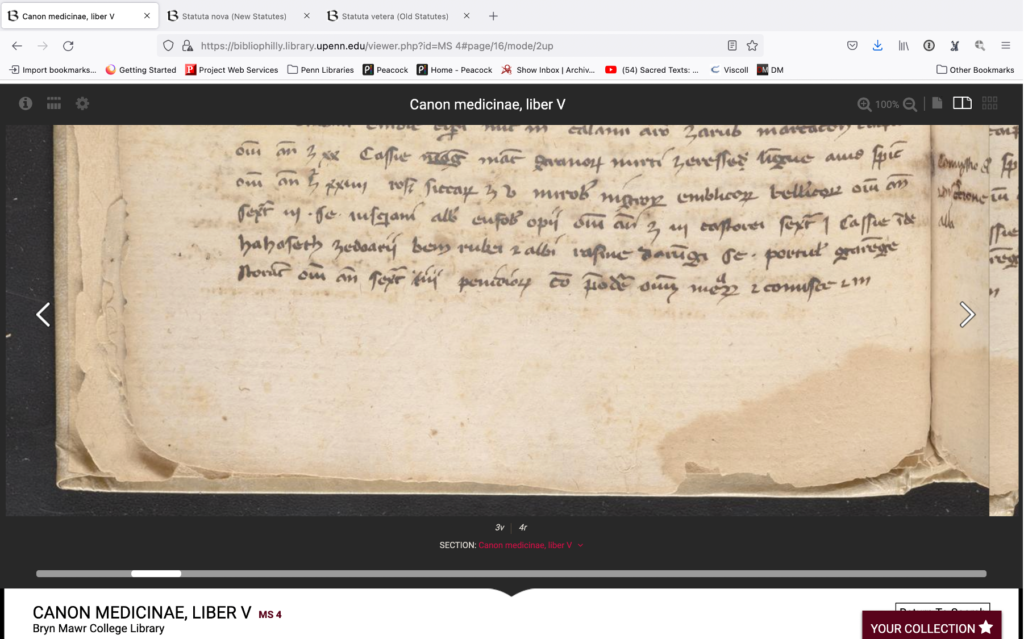

And then finally this last example, Bryn Mawr Ms. 4, is a paper manuscript. You should be able to tell, if you’ve studied paper, because there a chain lines there and also the way the paper is wearing around the edges. Parchment doesn’t flake like that, paper does that and being able to recognize that has nothing to do with whether you’re looking at it in person or in a digital image it looks the same either way. Whether or not you can tell the difference has more to do with your own training than with the fact that it’s an image. Now, we could talk about image quality, but most images that you access from an institution will be digitized to some set of best practices and guidelines. The images will also be presented alongside metadata – so if you’re not sure whether it’s paper or parchment, you can take a peek at the metadata and it will tell you.

One of the things I like to talk about when I discuss digitized manuscript is the concept of mediation, how one of the things that digitization does is it mediates our experience with the physical object. The people who play a part in that mediation – photographers, and software developers who build the systems and interfaces, and catalogers. Metadata is another example of that. We trust that the mediation is being done effectively; we trust that the cataloger knows the difference between parchment and paper and that this information is correct.

Ink can definitely be an issue in digitization, but I’m going to step sideways and talk instead for a moment about gold leaf. Gold leaf is notoriously difficult to photograph in the way that manuscripts are normally digitized – in a lab, on a cradle or a table, perhaps with a glass plate between the book and the camera holding the page flat. But gold leaf was made to move, was made to be seen in candlelight where it would gleam.

Here is an example of the difference between the same page digitized in a lab vs. an animated gif taken in a classroom – and yes, this is the same page (Ms. Codex 2032, f. 60r). While the gold in the gif shines when it is passed through the light, the gold in the still image looks almost black. Two things: again, because I’m trained, I know that’s gold in the still image even though it doesn’t look like gold, because I know what can happen to the appearance of gold when it’s photographed under normal lab conditions. And now you do, too. Just because it doesn’t shine like gold doesn’t mean it isn’t gold. Two, we don’t include images like the first one in our record, and that’s a choice. We make lots of choices about what we include and what we don’t, many of them made because of time issues or cost. We could make different decisions, we could choose to include images taken under different sorts of lighting and include them in the record, the technology is there.

“Often we can’t tell what the overall structure of the work is like, how many leaves it has, and whether it contains any cancelled leaves…”

A. S. G. Edwards, “Back to the real”

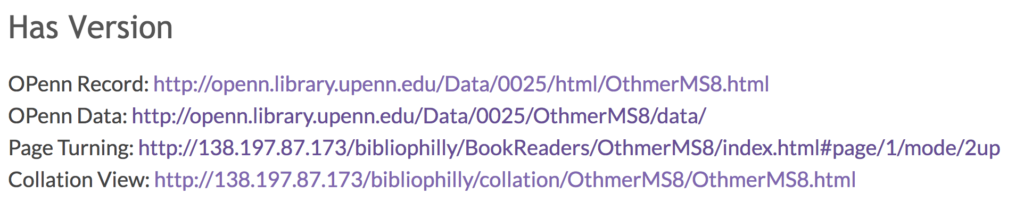

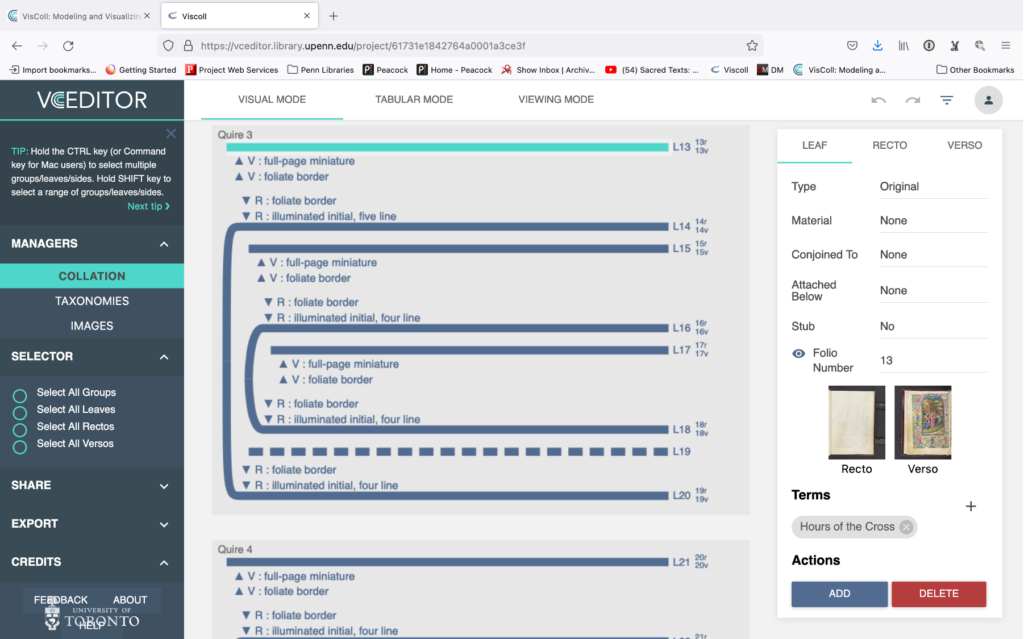

Now it’s really my time to shine because this concern about the loss of the structure of manuscripts in digitization is why I started the VisColl project with Alberto Campagnolo and Doug Emery back in 2013; it was one of the first things I did after I came to work at Penn.

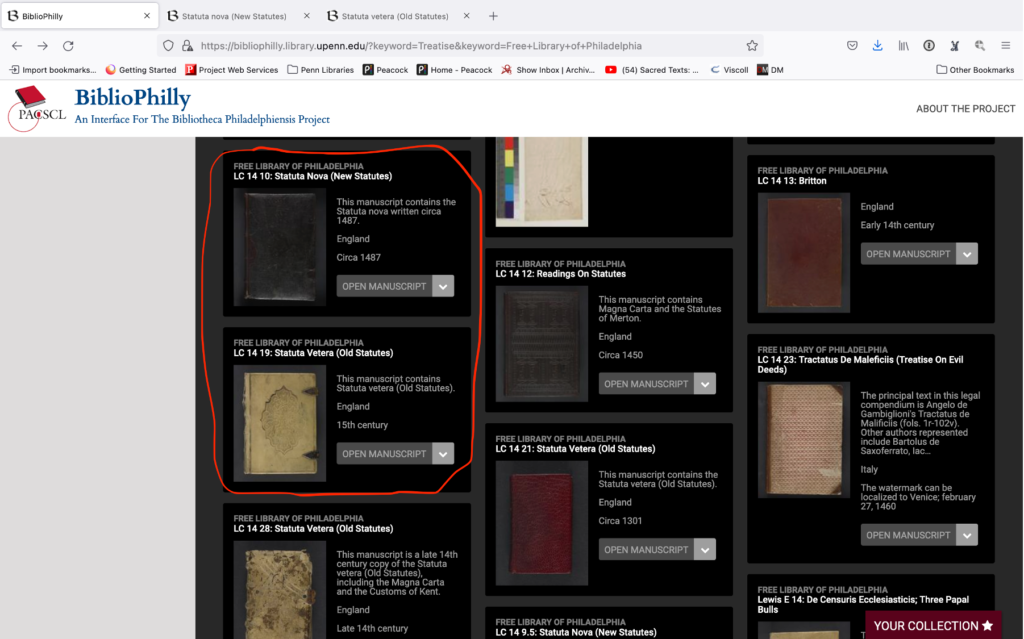

The aim of the VisColl project has been to create a data model and a software system for modeling and visualizing the structure of codex manuscripts. You can use on your own to help you with the study of individual manuscripts but it was also designed for use by manuscript catalogers, and in fact has been used in the BiblioPhilly project to create models that are presented alongside or integrated with the usual sort of page turning digital interfaces for manuscript collections, to provide a different kind of view. This sort of view that Edwards was concerned about, something that enables us to see what the structure is and see how long the manuscripts are.

So we’ll go back again to the statutes manuscripts. I mentioned earlier that I know that old statutes manuscripts are smaller than new statutes manuscripts both in terms of physical size of the covers and also in the size of the text and that is reflected here. The old statutes manuscript on the left has 21 quires, mostly of eight leaves, and the new statutes manuscript has 52 quires, also of eight leaves. It is a very large manuscript, a thick manuscript, and VisColl provides a way for us to show this size in our interfaces in a way that isn’t normally done.

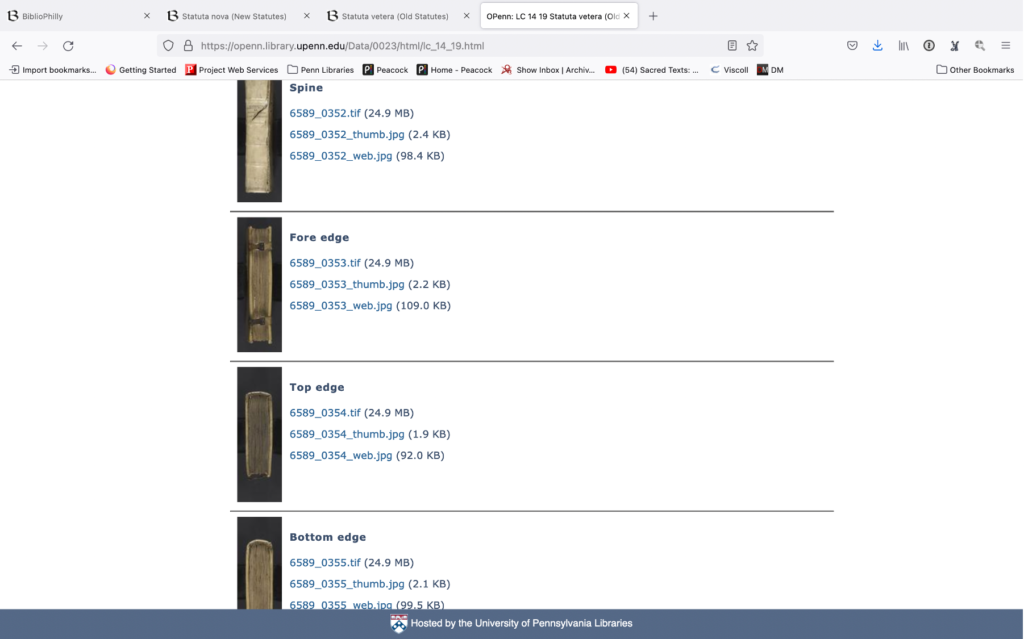

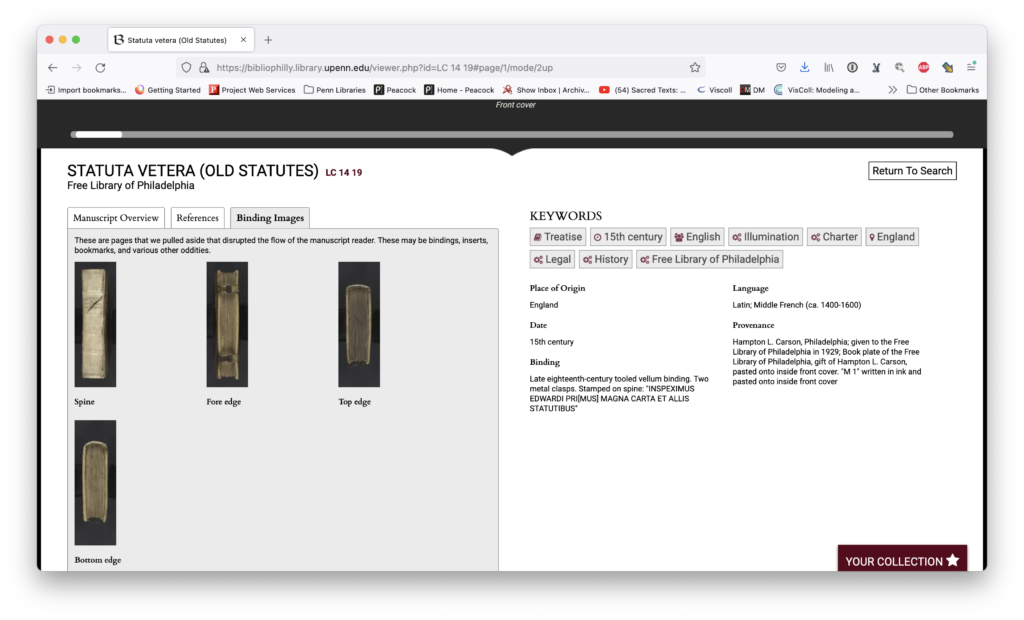

But making a model with VisColl is work, and it is not the only way to see the size of a manuscript. You can also tell the size of a manuscript by looking at its spine and edges, and this is coming around again to the issue of the choices that we – we, the institutions and libraries – make when we present these manuscripts.

This is a gallery view for LC 14 19 in the BiblioPhilly interface. If you scroll all the way to the end of the manuscript you can see that the presentation ends with the back cover, which makes sense, since when we close a book we see the back cover. But if we go look at the same manuscript in OPenn, which is the collection on our website where we make the data available, you’ll see that there are more images of the book there. BiblioPhilly takes this data and makes an interface that’s user-friendly, but OPenn is more like a bucket of stuff.

So we go to the bucket of stuff and we scroll down to the images and here are all the images, no page turning interface just image after image. We scroll all the way down and we’re going to find some images that don’t appear on the interface. There are images of the spine and the fore edges. These are available but we made a decision not to include those in the main BiblioPhilly interface, neither in the page-turning view or in the gallery view.

These are available in BiblioPhilly but you have to go to the “Binding Images” tab to find them. You have to know to go there; they are categorized as something different, something special, and not part of the main view. This is another choice that we made in designing the interface.

“… and we can rarely be confident that the colours have been reproduced accurately.”

A. S. G. Edwards, “Back to the real”

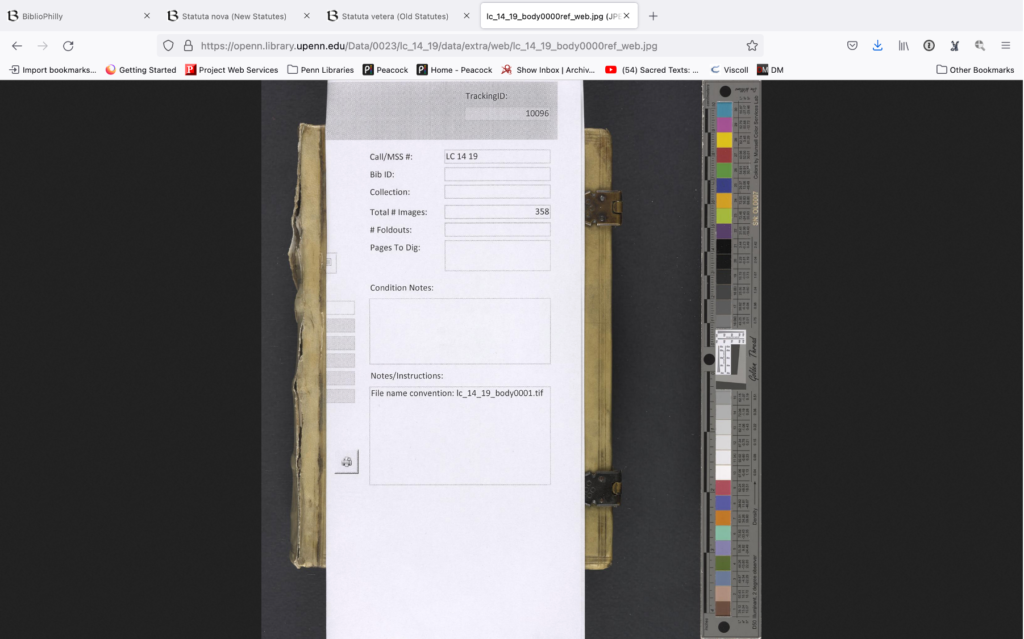

I can report that at this point in time there are standards and guidelines and best practices for ensuring that digital images have color correction checked against the manuscript. One of the ways that we ensure this is by including a color bar in either a reference image or occasionally in every single image. There are institutions, I believe that the British library is one of these, where you will see a color bar in every single frame.

At Penn we do include color bars and photographs but they are trimmed out as part of post processing. We do however maintain reference images that, as well as the photos of the spine and the fore edges, are available on OPenn and you can see them here. So here is a reference image for the old statutes manuscript that we’ve been looking at. In addition to being a color correction aid, the color bar also serves as a ruler. So here you can see that the color bar is longer than the manuscript.

Now if we look at the reference image for the new statutes manuscript you’ll see how much larger the book is in reference to the color bar. So this is getting back again to our starting issue of how big is the manuscript. It’s possible to see how big the manuscripts are because we have these reference images, but sometimes they are hard to find in the interface. And again this comes down to the decisions that we are making in terms of what is easy for you the user to see and find in our collections and through our interfaces.

Size information also comes along in the metadata. We’ve already looked at the metadata before when we were looking at the paper versus parchment question, and you can see here we also have information about the physical size of the manuscript. So even if you can’t tell by the cues in the image, if you don’t know anything about the genre which might help you know the size the physical size, if you don’t have access to a reference image with some kind of ruler or color bar that might give you an indication of the size, you might still have information in the metadata that should be easily accessible in whatever interface you’re using.

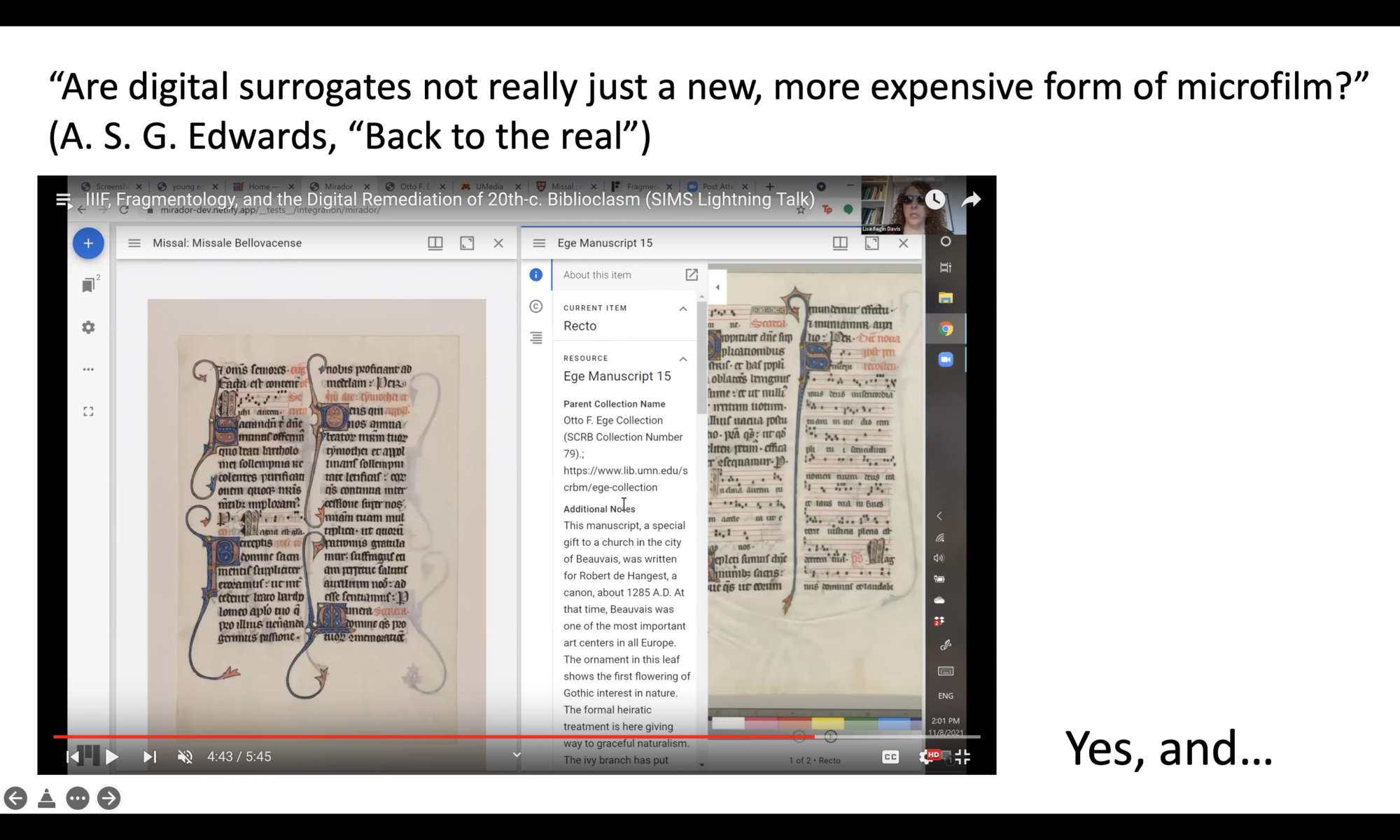

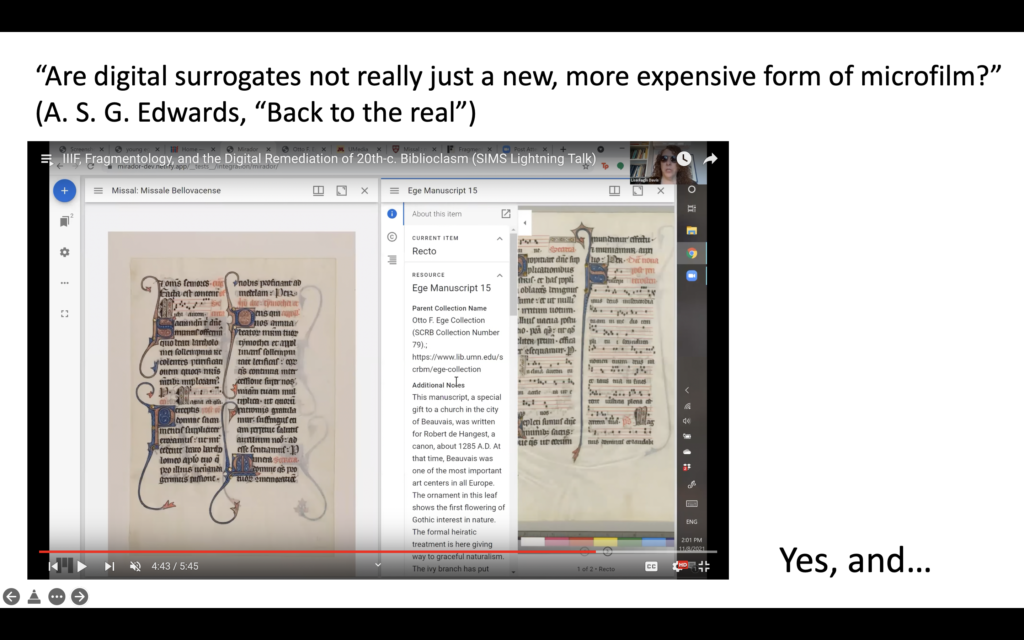

And now I want to start the pivot to the Schoenberg Symposium lightning talks (click here for the complete playlist) because one of our lightning talk speakers talks quite a bit about metadata and image coming along together. Lisa Fagin Davis in her talk “IIIF, Fragmentology, and the Digital Remediation of 20th-c. Biblioclasm” talks about IIIF, which I’ve already mentioned, the international image interoperability framework, and it’s use particularly with fragments in the study of what we’re now calling fragmentology. In her lightning talk, Dr Davis talks about how you can add images to a shared interface and it brings the metadata along with it. All of this current contextual information that Edwards was very worried about actually becomes an integral part of image sharing. So in IIIF you’re not just sharing an image file you’re sharing a lot of information along with it.

The last word that I want to give to Dr. Edwards is his final comments in this section of his piece. He says a lot more after this but I really love this question: “Are digital surrogates not really just a new, more expensive form of microfilm?” To which I say yes, and…

There’s just so much that you can do with digitized images and our lightning talks speak to this so I want to go through the lightning talks and talk about how their concerns answer or reflect Edwards’s own concerns.

Including Lisa’s talk, three other talks focus on interacting with digital images in platforms to work towards a scholarly aim. Chris Nighman from Wilfrid Laurier University in his talk “Loss and recovery in Manuscripts for the CLIMO Project” gives an overview of his project to edit Burgundio of Pisa’s translation of John Chrysostom’s homilies on the Gospel of Matthew, which he rendered at the request of Pope Eugenius III in 1151. The apparent presentation copy Burgundio prepared for the pope survives as MS Vat. lat. 383, which is provided online by the BAV, but unfortunately the manuscript is lacking two pages. However Nighman is able to restore the text from another copy of the same text, MS Vat. lat. 384, which is also available online.

In her talk “A Lost and Found Ending of the Gospel of Mark,” Claire Clivaz presents the Mark 16 project, which is seeking to create a new edition – the first edition – of the alternative ending of the Gospel of Mark, which although well attested in many languages, is usually ignored by scholars as being marginal or unimportant. And in their talk “Lost in Transcription: EMROC, Recipe Books, and Knowledge in the Making,” Margaret Simon, Hillary Nunn, and Jennifer Munroe illustrate how they are using a shared transcription platform, From the Page, to create the first complete transcription of the Lady Sedley’s 1686 manuscript recipe book, which has only been partially transcribed in the past, the sections of the text relating to women’s concerns in particular having been ignored.

In all four of these talks, rather than expressing discontent on the loss that happens when materials are digitized, (or, in Chris Nighman’s talk, complaining about the watermarks added by the Vatican digital library), the presenters are using digital technology to help fill in losses that are wholly unrelated to digitization.

In her talk “Loss and Gain in Indo-Persian Manuscripts,” Hallie Nell Swanson provides a fascinating overview of the various ways that Indo-Persian manuscripts have been used and misused, cut apart and put back together, over time. For her, digitization is primarily useful as an access point; until recently, Swanson has only been able to access these books virtually, and yet she’s able to make compelling arguments about them.

Kate Falardeau’s talk, “London, British Library, Add. MS 19725: Loss and Wholeness,” is particularly compelling for me, because I wonder if it’s the kind of presentation that would only be made in a digital context, although the paper itself is not “digital.” Digitization has normalized fragmentation in a way not seen before now; we’re used to seeing leaves floating around, disbound and disembodied, and Kate’s argument that an incomplete, fragmentary copy of Bede’s Martyrology might nevertheless be considered whole within its own context is an idea that works today but might not have been conceived at all back in 2013.

In another non-digital talk that uses digital technology in a completely different way, William Stoneman presents on “George Clifford Thomas (1839-1909) of Philadelphia: Lost in Transition,” a 19th century bibliophile who is often overlooked within the context of the history of Philadelphia book collecting, even though the books he owned later passed through more well-known hands and now reside in some of the world’s top libraries. Stoneman points to the Schoenberg Database of Manuscripts, directed by my colleague Lynn Ransom, which is a provenance database, that is it traces the ownership of manuscripts over time – including manuscripts owned by George Clifford Thomas.

In his entertaining and illuminating talk, “Extreme Loss and Subtle Discoveries: The Corpus of Sotades of Maronea,” Mark Saltveit presents on recently discovered lines of text by the ancient poet Sotades – discoveries that were made entirely by reconsidering quotes and identification of poets in earlier texts, and not at all through any kind of digital work (which is part of his point)

Finally, of all the Lightning Talks, Mary M. Alcaro takes a more critical approach in her talk “Closing the Book on Kanuti: Lost Authorship & Digital Archives.” This Kanuti, we discover, was attributed the authorship of “A litil boke for the Pestilence” In the 15th century, and this authorship followed the text until 2010, when Kari Anne Rand said in no uncertain terms that this Kanuti was not the author. But no matter – online catalogs still list him as the author. A problem for sure!

I want to close by pushing back a little on the accepted knowledge that digitization only causes loss. I think it does, but there are other ways that we can talk about digitization too, which may sit alongside the concept of loss and which might help us respond to it.

I’ve talked about mediation a bit during this talk – the idea that the digitized object is mediated through people and software, and this mediation provides a different way for users to have a relationship with the physical object. The decisions that the collection and interface creators make have a huge impact on how this mediation functions and how people “see” manuscripts out the other side, and we need to take that seriously when we choose what we show and what we hide.

Transformation: basically, digitization transforms the physical object into something else. There is loss in comparison with the original, but there is also gain. It’s much easier to take apart a digital manuscript than a physical one. About that…

I’ve talked before about how digitization is essentially a deconstruction, breaking down a manuscript into individual leaves, and interfaces are ways to reconstruct the manuscript again. It’s typical to rebuild a manuscript as it exists, that’s what we do in most interfaces, but it also enables things like Fragmentarium, or VisColl, where we can pull together materials that have long been separated, or organize an object in a different order.

Finally, my colleague Whitney Trettien, Assistant professor of English at Penn, claims the term creative destruction (currently used primarily in an economic context) and applies it to the work of the late seventeenth century shoemaker and bibliophile John Bagford, who took fragments of parchment and paper and created great scrapbooks from them – as she says in this context, “creative destruction with text technologies is not the oppositional bête noire of inquiry but rather is its generative force.”[2] Why must we insist that digitized copies of manuscripts reflect the physical object? Why not claim the pieces as our own and do completely new things with them?

Digitization is lossy, yes. But it can also generate something new.

I must say that to see a manuscript will never be replaced by a digital tool or feature. A scholar knows that a face to face meeting with a manuscript is something that can be replaced by nothing else.

Claire Clivaz, “A Lost and Found Ending of the Gospel of Mark”

Claire Clivaz is correct – a digital thing will never replace the physical object. But I think that’s okay; it doesn’t have to. It can be its own thing.

[1] Edwards, A. S. G. “Back to the real?” The Times Literary Supplement, no. 5749, 7 June 2013, p. 15. The Times Literary Supplement Historical Archive.

[2] Trettien, Whitney. “Creative Destruction and the Digital Humanities,” The Routledge Research Companion to Digital Medieval Literature and Culture, Ed. Jen Boyle and Helen Burgess, 2018, pp. 47-60.