It’s not that I haven’t been doing anything; I just haven’t been doing anything here.

In June, Tim Stinson at NCSU and I were awarded a grant from the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation to implement the Medieval Electronic Scholarly Alliance, MESA, and since we started preparing metadata for indexing in, oh, about mid-September, all of my technical energy has been going into that work. MESA is a node of the Advanced Research Consortium (ARC), and follows the model of scholarly federation spearheaded by NINES and followed by 18thconnect, using Collex as its underlying software support.

What does it involve? It involves taking metadata already created by digital collections or projects (like, for example, the Walters Art Museum, Parker on the Web, or e-Codices), mapping their fields out to the Collex and MESA fields, and then generating RDF that follows to the Collex guidelines. It’s these three collections (and, just in the last week and with a ton of help from Lisa McAulay at UCLA, the St. Gall Project) that I’ve spent the most time on, and here are some key things I’ve learned so far that might be helpful for people considering adding their collections to MESA (or to any of the other ARC nodes, for that matter)… or for that matter, for anyone who is interested in sharing their data, any time ever.

- If your metadata is in an XML format, put unique identifiers on all the tags. Just do it.

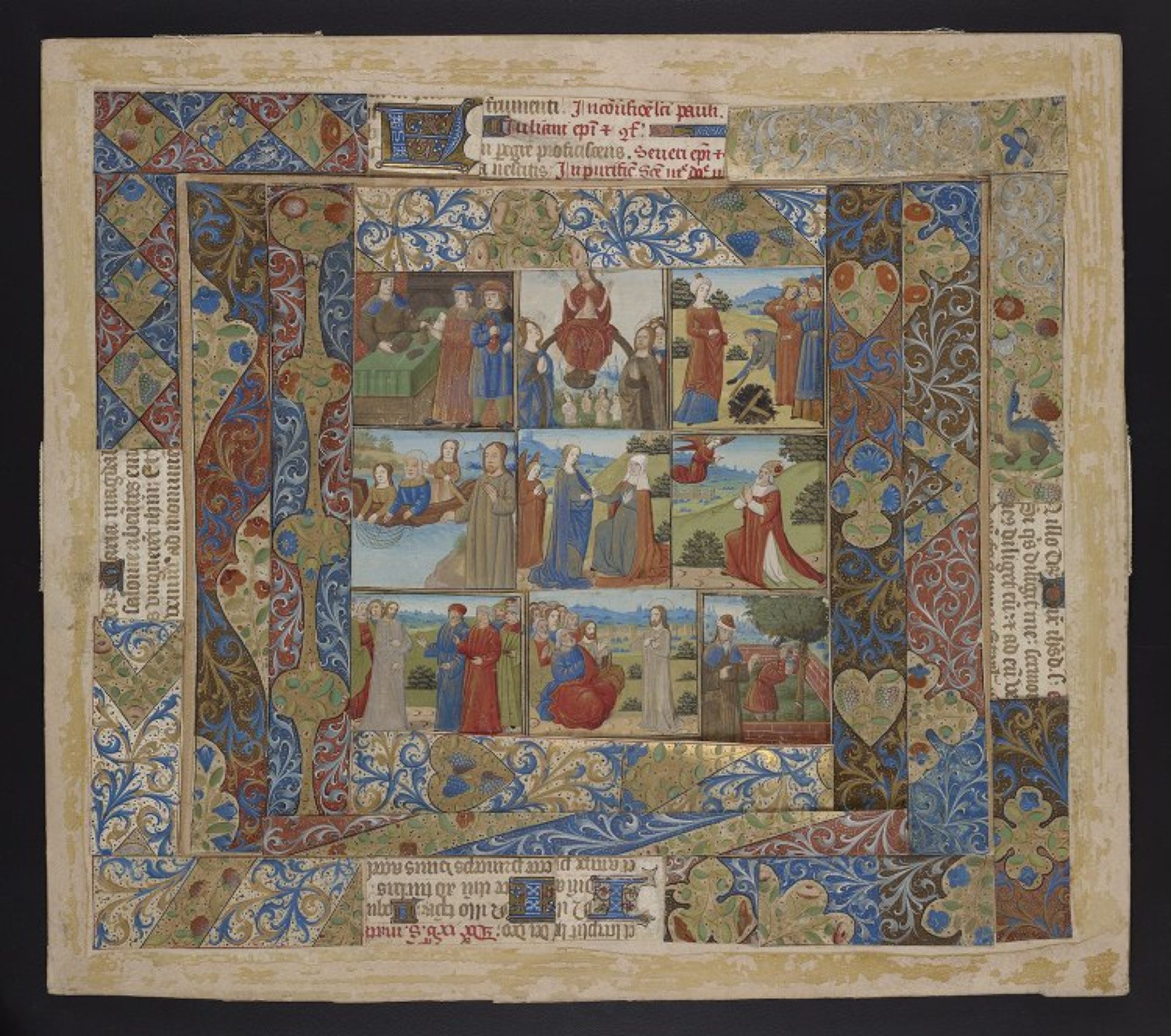

- Follow best practices for file and folder naming. In this case, best practice probably just means BE CONSISTENT. My favorite example for illustrating consistency is probably the Digital Walters at the Walters Art Museum. One of the reasons that it’s a great example is that their data (image files and metadata) has been released under Open Access licensing, with the intention that people (like me) will come along and grab them, and work with them. What this means is that everything was designed with this usage in mind, so it’s simple, and that all their practices are well-documented, so it’s easy to take them and run without having to figure a lot out. Their file and folder naming practices are documented here.

- Be thoughtful about how you format your dates. Yeah, dates are a big deal. The metadata of one of the projects (I won’t say which one) had dates formatted as, e.g., “xii early-xiii late (?)”, and with no ISO (or an other even slightly computer-readable) version in, e.g., an attribute value. I ended up mapping every individual date value to a computer-readable form. As always, I figure there was a better way to do it, but at the time… well, it took a while, but in the end it did what I needed it to do. If you are in the process of setting up a new project, consider including computer-readable dates in your metadata. Because Collex/MESA includes values for both date label and date value, you can include both a computer-readable date to be used for searching, and a human-readable version, which may have more nuance than can be included in a computer readable value. For example, LABEL: xii early-xiii late (?); VALUE: 800,900.

- Is whatever you are describing in English? Great! If it’s not, find someplace in your metadata to indicate what language it is in. Use a controlled vocabulary, such as the ISO 639-2 Language Code List, and as with dates it helps to include a computer-readable code in addition to a human-readable version. (This is less important for MESA, as we can map between the columns in the ISO 639-2 Language Code List, but it’s a good general rule to follow)

- You can actually do a lot with a little. In the past few weeks the metadata I’ve worked with range from really amazing full manuscript Descriptions (in TEI P5) from the Walters Art Museum to very simple and basic descriptions in Dublin Core from e-Codices. Although the full descriptions provide more information (helpful for full-text searching), the simple DC records, assuming they include the basic information you’d want for searching (title, date, language, maybe incipits) are just fine. So don’t let a lack of detail put you off from contributing to MESA!

I would also encourage you to release your data under an Open Access license (something from the Creative Commons), and to make your data easy to grab (either by posting everything online, as the Walters Art Museum has done, or by releasing it through an OAI provider, as e-Codices has done).