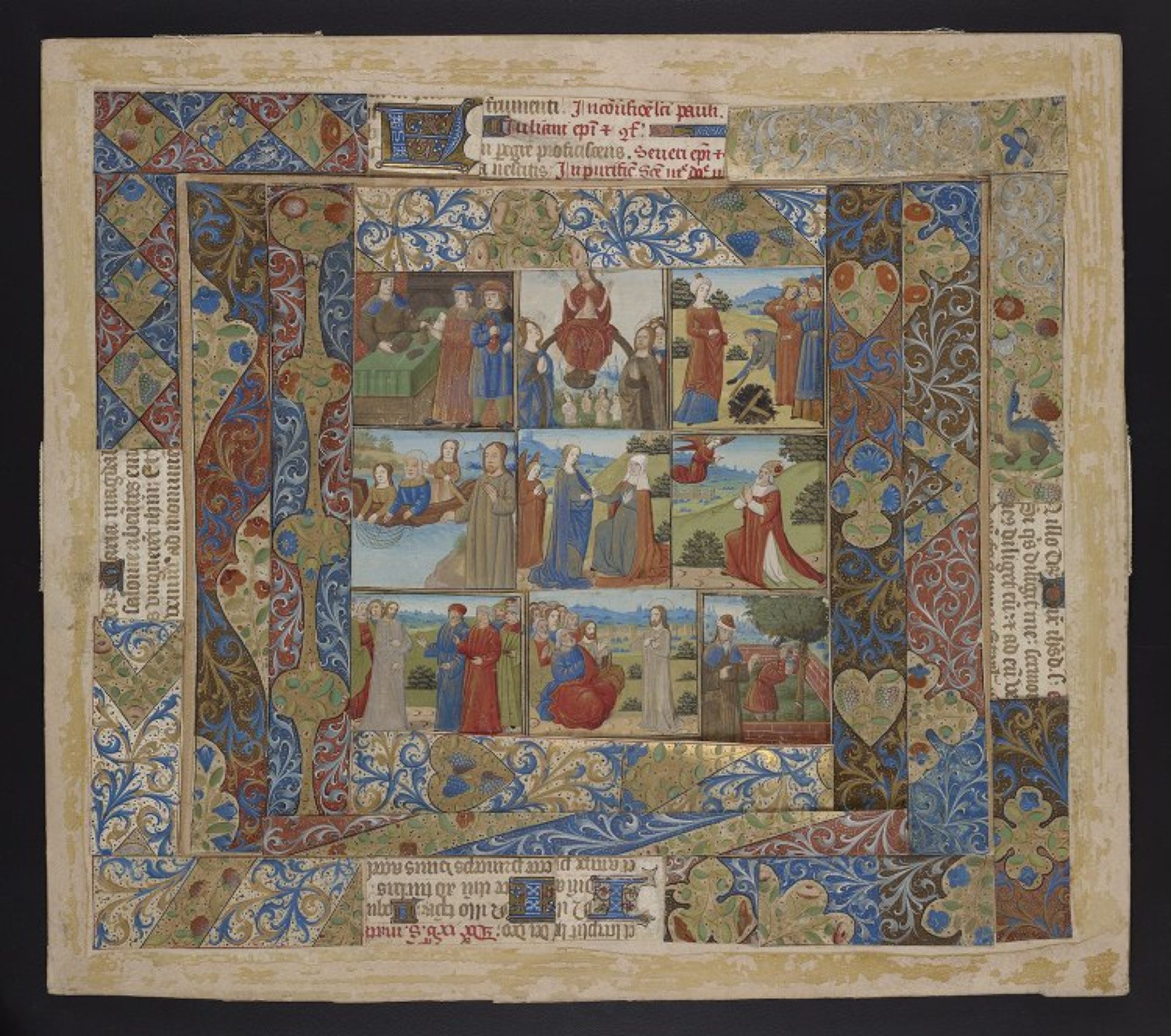

This is a version of a paper presented at the International Congress on Medieval Studies, May 12, 2018, in session 482, Digital Skin II: ‘Franken-Manuscripts’ and ‘Zombie Books’: Digital Manuscript Interfaces and Sensory Engagement, sponsored by Information Studies (HATII), Univ. of Glasgow, and organized by Dr. Johanna Green.

Continue reading “Zombie Manuscripts: Digital Facsimiles in the Uncanny Valley”Workflow: MS Word to TEI

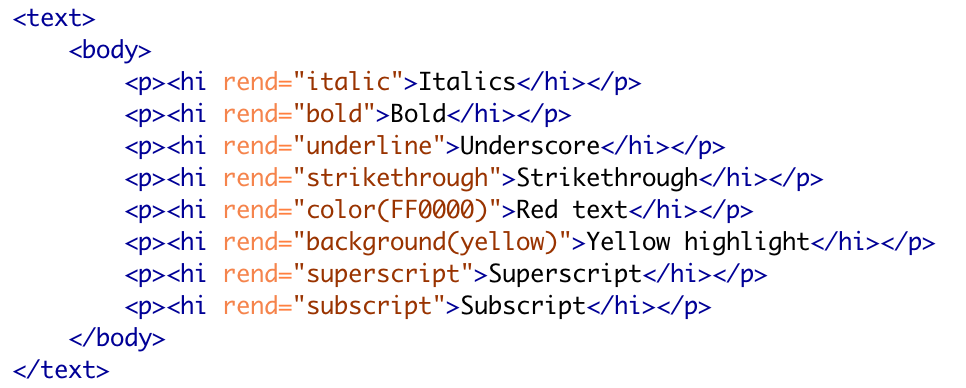

For the past couple of years I’ve been refining a workflow to convert MS Word files into publishable TEI. By “publishable” I mean TEI that can be loaded into some existing publication system (something like TEI Publisher, Edition Visualization Technology (EVT), or TEI Boilerplate), or that you could process yourself in some other way.

Continue reading “Workflow: MS Word to TEI”Using VisColl to Visualize Parker on the Web: Reports on an experiment

This is the full text of a talk I presented at the Parker on the Web 2.0 Symposium in Cambridge on March 16, 2018 (Please note addendum at the end which addresses an issue that came up in discussion later in the day.)

Continue reading “Using VisColl to Visualize Parker on the Web: Reports on an experiment”“What is an edition anyway?” My Keynote for the Digital Scholarly Editions as Interfaces conference, University of Graz

This week I presented this talk as the opening keynote for the Digital Scholarly Editions as Interfaces conference at the University of Graz. The conference is hosted by the Centre for Information Modelling, Graz University, the programme chair is Georg Vogeler, Professor of Digital Humanities and the program is endorsed by Dixit – Scholarly Editions Initial Training Network. Thanks so much to Georg for inviting me! And thanks to the audience for the discussion after. I can’t wait for the rest of the conference.

Continue reading ““What is an edition anyway?” My Keynote for the Digital Scholarly Editions as Interfaces conference, University of Graz”