This blog post was originally conceived as a contribution to Now You See It Now You Don’t: Sustainable Access in a Digital Age, an event organized by the Bodleian Library and held on Zoom on February 7, 2024. Although my name appears in the list of contributors, I caught the flu that week and wasn’t able to attend. But I was prepared, and even though I’ve no doubt other people there said similar things, I wanted to post this for FOMO if for no other reason. This post consists of screenshots of my slides, and accompanying notes that explain my points further.

Welcome to my talk, “Collections Sharing as a form of Digital Collections Security.” Thank you to Laura Morreale and Stewart Brookes for inviting me. I come to the group as a curator whose responsibilities include premodern manuscripts and digital collections, so the effects of the shutdown at the British Library, particularly the inaccessibility of their manuscripts for the duration, was of particular interest to me and was felt strongly in my circles.

One of the benefits of digital collections over physical collections is that digital collections can be copied, and these copies can exist in many places at once. By Collection Sharing I mean digital collections from one institution (in the medieval manuscript world, this usually means: digital copies of manuscripts owned by that institution) being shared and available in systems at other institutions, in a way not dependent on the systems of the original institution. For reasons of sustainability, that last point is important (and it means that IIIF systems don’t count). In order to enable Collection Sharing, institutions need to rethink their licensing, reconsider what “our collections” are (i.e., expanding “our collection” from only those things that we physically own) and cultivate a willingness to share their own digital materials.

Collection Sharing is pretty popular. The Internet Archive includes copies of many institution’s digital collections, including the Bibliotheca Philadelphiensis project, which includes over 450 digitized manuscripts from institutions around Philadelphia.

While the British Library collections aren’t in the Internet Archive, they have been known to practice Collection Sharing. The Digitized Hebrew Manuscripts, for example, are not only available through the BL’s website, but they’re also able to be downloaded through the BL’s data repository.

Vitally, these collections are all in the public domain. This means there are no licensing restrictions on them, and anyone is free to use them however they wish.

This means that both individuals and other institutions, such as the National Library of Israel, can download the images and metadata for those manuscripts and make them available in their own systems. If the BL library systems go down, these manuscripts are still available through the National Library of Israel.

The University of Pennsylvania hosts OPenn, which is a website containing raw digital data (images and metadata) for manuscripts that Penn owns and also collections owned by other institutions. All materials on OPenn are in the public domain or released under Creative Commons licenses as Free Cultural Works.

As it happens, Penn also has a pretty great collection of Judaica manuscripts; as of the date of posting, 245 manuscripts in OPenn are from the Library of the Katz Center for Advanced Judaic Studies at Penn, and there are more Judaica holdings in other collections at the Kislak Center for Special Collections, Rare Books, and Manuscripts (which is the umbrella unit for both the Katz Center Library and SIMS). (Search for cajs in this page.)

OPenn contains the Katz Center collection, the Kislak collections, and collections for other institutions as well. For example, OPenn includes items from the archives of Congregation Mikveh Israel, the oldest Jewish congregation in Philadelphia dating from the 1740s. This collection and others contribute to the collection development priorities of the Kislak Center–the holding institutions keeps the original materials and gains digital copies, and we get digital copies, too.

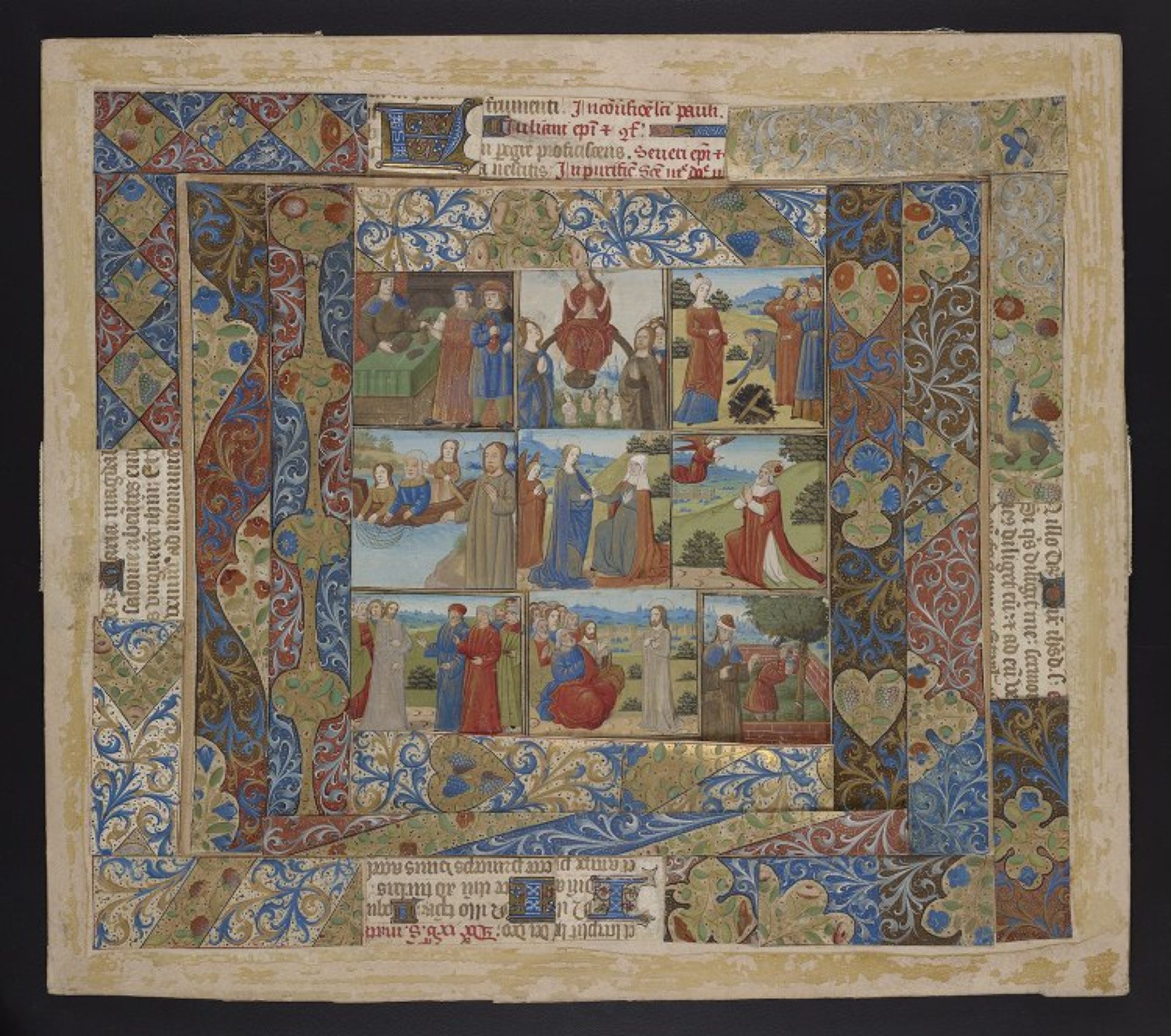

Since the Hebrew collections at the BL are in the Public Domain, and since they also serve the Judaica collection development interests of the Kislak Center, in 2019 we decided to include them in OPenn, too. We downloaded the metadata and images from the BL data repository, converted their TEI into spreadsheets which we imported into our system and then converted back into OPenn TEI, and loaded everything into OPenn. This is a video scrolling through the record for BL Add MS 11668.

Now the BL’s Hebrew manuscripts are part of OPenn’s collections. They fit in with the Kislak Judaica collections, and they are licensed in a way that suits OPenn’s requirement that included materials be Free Cultural Works.

Collection Sharing as described in this post isn’t exactly new. Some of you may be familiar with LOCKSS, Lots of Copies Keeps Stuff Safe. Unlike Collection Sharing, which relies on the host library’s collection development interests and using existing infrastructure to serve shared materials in the same way the host shares their own materials, LOCKSS is primarily a set of shared technologies that distribute files for digital preservation.

I hope more institutions consider sharing and hosting their digital collections. If your institution’s systems crash, it’s good to know that your collections will be available elsewhere.