This talk was presented as part of a panel at the Global Digital Humanities Symposium at Michigan State University, March 16-17 2017: ARC Panel: Access, Data, and Collaboration in the Global Digital Humanities

My story begins in 2012, when Dr. Benjamin Fleming, Visiting Scholar in Religious Studies and Cataloger of Indic Manuscripts for the Kislak Center for Special Collections at the University of Pennsylvania, proposed and was awarded an Endangered Archives grant from the British Library. The main purpose of the grant was to write a catalog for the Ramamala Library, which is one of the oldest still-active traditional libraries in Bangladesh. A secondary part of this grant was to digitize around 150 of the most fragile manuscripts from the Ramamala Library, and an agreement was made that the University of Pennsylvania Libraries would be responsible for hosting these digital images. At this time, someone from the Penn libraries recommended to Dr. Fleming that they get a Creative Commons license, and the non-commercial license was given as an example. The proposal went forward with a CC-NC license, which both the Penn Libraries and the Ramamala Library agreed to, and everything was fine.

So a bit of historical logistics might be helpful here. 2012, the year this proposal was agreed to, was one year before the Schoenberg Institute for Manuscript Studies (SIMS) was founded at Penn. One of the very first things that SIMS was tasked with doing – one of the things it was designed to do – was to create some kind of open access portal to enable the resue of digital images of our medieval manuscripts. Penn has been digitizing our manuscripts and posting them online since the late 1990s, and in 2013 all of them were online in a system called Penn in Hand. Penn in Hand is a kind of black box – you can see the manuscripts in there, search for them, navigate them, but if you want to publish an image in a book or use them in a project, you have to do some work to figure out what’s allowed in terms of licensing, and then figure out how to get access to high-resolution images that are going to be usable for your needs.

It took us a couple of years, but on May 1, 2015, we launched OPenn: Primary Digital Resources Available for Everyone, as a platform not for viewing images, but explicitly for downloading and reusing images and metadata. OPenn includes high-resolution master TIFF images and smaller JPEG derivatives, as well as robust metadata in TEI/XML using the Manuscript Description element. We started hosting our own data, but today we host manuscript data for 17 institutions in the Philadelphia area with others in the US and Europe (including Hebrew manuscripts from the John Rylands Library at the University of Manchester) to come online in the next year. One the things we wanted was for users of OPenn to always be certain about what they could do with the data, so we decided that anything that goes into OPenn must follow those licenses that Creative Commons has approved for Free Cultural Works:

- the CC Public Domain mark

- CC0 (“CC-zero”), the Public Domain dedication for copyrighted works

- CC-BY, the Creative Commons Attribution license

- CC-BY-SA, the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike license

Note that licenses with a non-commercial clause are not approved for Free Cultural Works, and thus OPenn, by policy, is not able to host them.

You see where this is going.

So in March 2016, a year after OPenn was launched, and well after the Ramamala Library manuscripts had been photographed, Dr. Fleming asked about adding the Ramamala Library material to OPenn, in addition to having it in Penn in Hand (where it was already going online). It wasn’t until he asked this question that we realized, under current policy, we couldn’t include that material in OPenn because of the license. Over the next few weeks we (we being representatives of OPenn, and Dr. Fleming) had several conversations during which we floated some various ideas:

- We could loosen the “Free Cultural Works” requirement and allow inclusion of the Ramamala data with the noncommercial license.

- We could build a parallel OPenn to contain data with a noncommercial license.

- We could use OPenn as a kind of carrot, to encourage the Ramamala library administration to loosen the noncommercial clause on the license and release the data as Free Cultural Works.

The third option was struck down almost as soon as it was suggested. There were, it turns out, highly sensitive discussions that had been happening at the Ramamala Library during the course of the project that would have made such a request difficult to say the least. As Dr. Fleming said in an email to me as we were talking about this talk, “It would be highly inappropriate and complex to try and revisit the copyright agreement as, even as it was, the act of a Western organization making digital copies of a small set of mss unraveled a dense set of internal issues related to private property and government control over cultural property (digital or otherwise).”

Before I return to our other two options I want to take a quick detour to talk a bit about how this conversation changed my thinking about Open Access in general, and about open access of non-Western material specifically.

I am by all accounts an evangelist for open access to medieval manuscript material. I like to complain: about institutions that keep their images under strict licenses, that make their images difficult or impossible to download, that charge hefty fees for manuscripts that have been digitized for years. OPenn is a reaction against that kind of thinking. We say: Here are our manuscript images! Here is our metadata! Here’s how you can download them. Do whatever you like with them. We own the books, but we acknowledge that they are our shared cultural heritage and in fact they belong to all of us. So the very least we can do is give you digital copies.

Until Ramamala, I would have told you that it was necessary that digital images of every manuscript in every culture that was written before modern times should be in the public domain and available for everyone. The people who wrote them are dead, and they wouldn’t have had the same conception of copyright ownership in any case, so why not? But suddenly I wasn’t so sure. I was forced to move beyond thinking in very black and white terms about “old vs. new” to thinking in a more nuanced way about “old vs. new”, sure, but also about “what is yours vs. what is ours” – and what ownership of the physical means for ownership of the digital. Again, until Ramamala I would have told you that physical owners owe it to the rest of us to allow the digital to sit in the public domain. But what does this mean for countries who have suffered under colonialism, and who have been forced for the past however many hundred years or more to share their cultural heritage with the west? In my somewhat unstructured thoughts, I keep coming back to the Elgin Marbles, which is just one example of cultural vandalism by the west (in this case, with the assistance of the Ottoman Empire, which ruled Greece at the time the marbles were taken) but is a particularly egregious one. I’m sure you’re all familiar with the Elgin Marbles, which used to decorate buildings in the Arcopolis, including the Parthenon, before they were removed to Britain between 1801 and 1812, later purchased by the British Museum where they can be seen today, although the current government of Greece has urged their return for many years.

Now the situation of the manuscripts in the Ramamala Library isn’t the same as that of the Elgin Marbles – we aren’t suggesting to move the physical collection to Penn – but I can’t help but believe there is a parallel here, and particularly a case to be made for respecting the ownership of cultural heritage by the cultures that created the heritage. But what does that mean? Dr. Fleming’s comment above implies the complexities around this question. Does “the culture that created the heritage” mean the current government? Or the cultural institutions? Or the citizens of the countries, or the citizens of the culture in those countries, no matter where they live now? And once we figure out the who, how do we ensure they have power to make decisions about their heritage objects? But I have taken my tangent far enough and I want to get back to talking about our ideas for making the Ramamala Library data available in OPenn.

When we left off, we had two other ideas:

- We could loosen the “Free Cultural Works” requirement and allow inclusion of the Ramamala data with the noncommercial license.

- We could build a parallel OPenn to contain data with a noncommercial license.

We considered the first suggestion but decided very quickly that we didn’t want to open that can of worms. Our concern was that if we started allowing one collection with a noncommercial license, no matter what the circumstances, other institutions that would want to include such a clause could point to it and say “Well them, why not us”? We have in fact used our “Free Cultural Works” only policy as a carrot for other institutions we host data for, including several museums and libraries in Philadelphia, and it works remarkably well (free hosting in exchange for an open license is apparently an attractive prospect). We don’t want to lose that leverage – particularly when it comes to institutions that own materials from former colonial countries, we have the ability and thus the responsibility to make that data available again, and it’s not a responsibility we take lightly.

The second idea, building a parallel OPenn to allow noncommercially licenced data, was more attractive but, we decided, just too much work at this time, with only one collection. However it did seem like something that would be a good community project: an open access portal, similar to OPenn in design, but with policies designed for the concerns surrounding access and reuse for cultural heritage data from former colonial countries. If something like this is currently being designed I would love to hear about it, and I expect we would be very happy to put our Ramamala data into such a platform.

So what did we do? We decided to take the path of least resistance and not do anything. The Ramamala manuscripts are available on Penn in Hand, and, since the license information was entered into the MARC record notes field, the license is obvious (unlike most other materials in Penn in Hand). The images are still not easily downloadable, although we are working on a new page for the project through which people can request free access to the high-resolution TIFF files. However, they aren’t available on OPenn. And I’m not sorry about that. I’m not sorry that OPenn’s policy is strictly for “Free Cultural Works,” because I think within our community, serving mainly institutions in Philadelphia and other US and Western European cities, the policy helps us leverage collections into Open Access that might otherwise be under more strict licenses. But I do think it’s important for us to keep talking and thinking about how we can serve other communities with respect.

Edit: after posting this talk, I was contacted by Caroline Schroeder who pointed me to an article she wrote about similar issues with Coptic manuscripts. I share a link to that article here: Caroline T. Schroeder, “Shenoute in Code: Digitizing Coptic Cultural Heritage For Collaborative Online Research and Study” Coptica 14 (2015), 21-36.

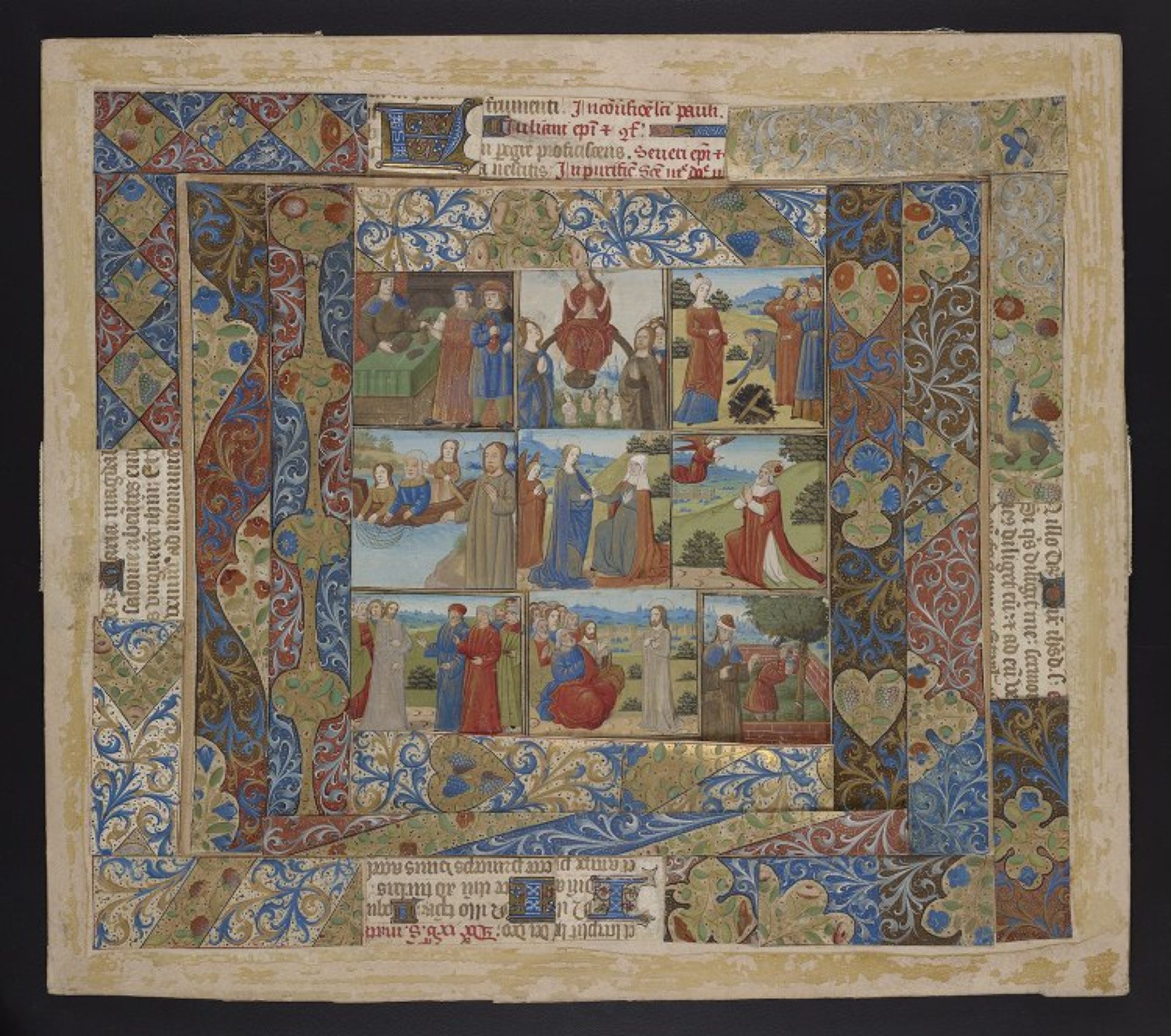

![Title: Initial "C" with St. Paul trampling Agrippa Form: Historiated initial "C," 12 lines Text: Psalm 97 Comment: The inscriptions on the scrolls read "Paulus/Agr[ipp]a." The second inscription is partially obliterated.](http://www.dotporterdigital.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/w36-89r-671x1024.jpg)