In March 2025, I presented a talk for the “Medievalia at the Lilly Library” annual event called “VCEditor as a Tool for Speculative Codicology.” I started the talk with a description of the VisColl Project, which is concerned with the practice and theory of modeling and visualizing the physical construction (aka collation) of codex manuscripts. Next, I talked about VCEditor, which is the current version of the software we use to build and visualize models (using the VisColl Data Model).

Continue reading “Speculative Codicology”Addendum: Full citations for Specific Knowledge post

This post serves as an addendum to Specific Knowledge: Cassandra Daucus on Manuscripts, published by From Beyond Press.

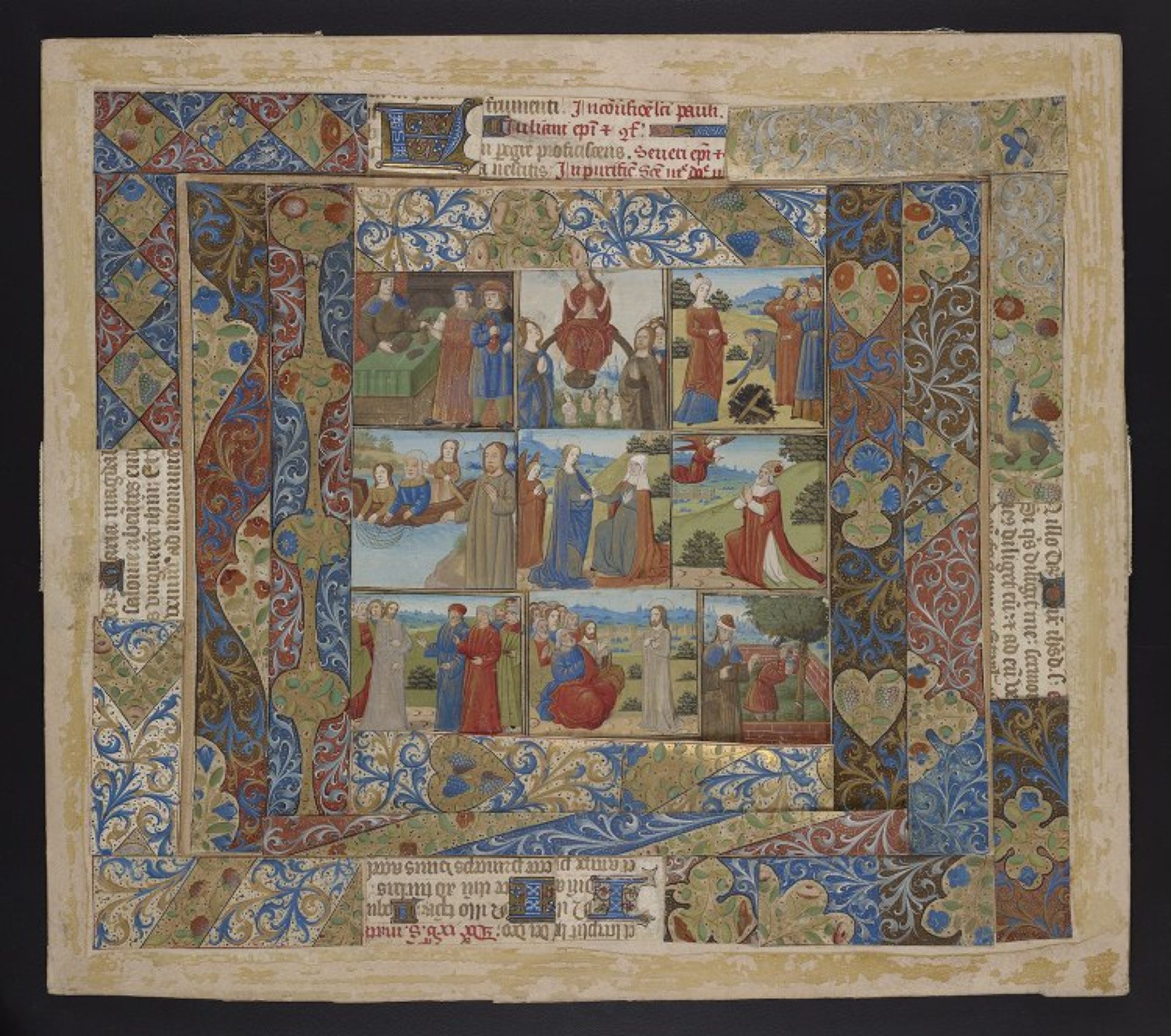

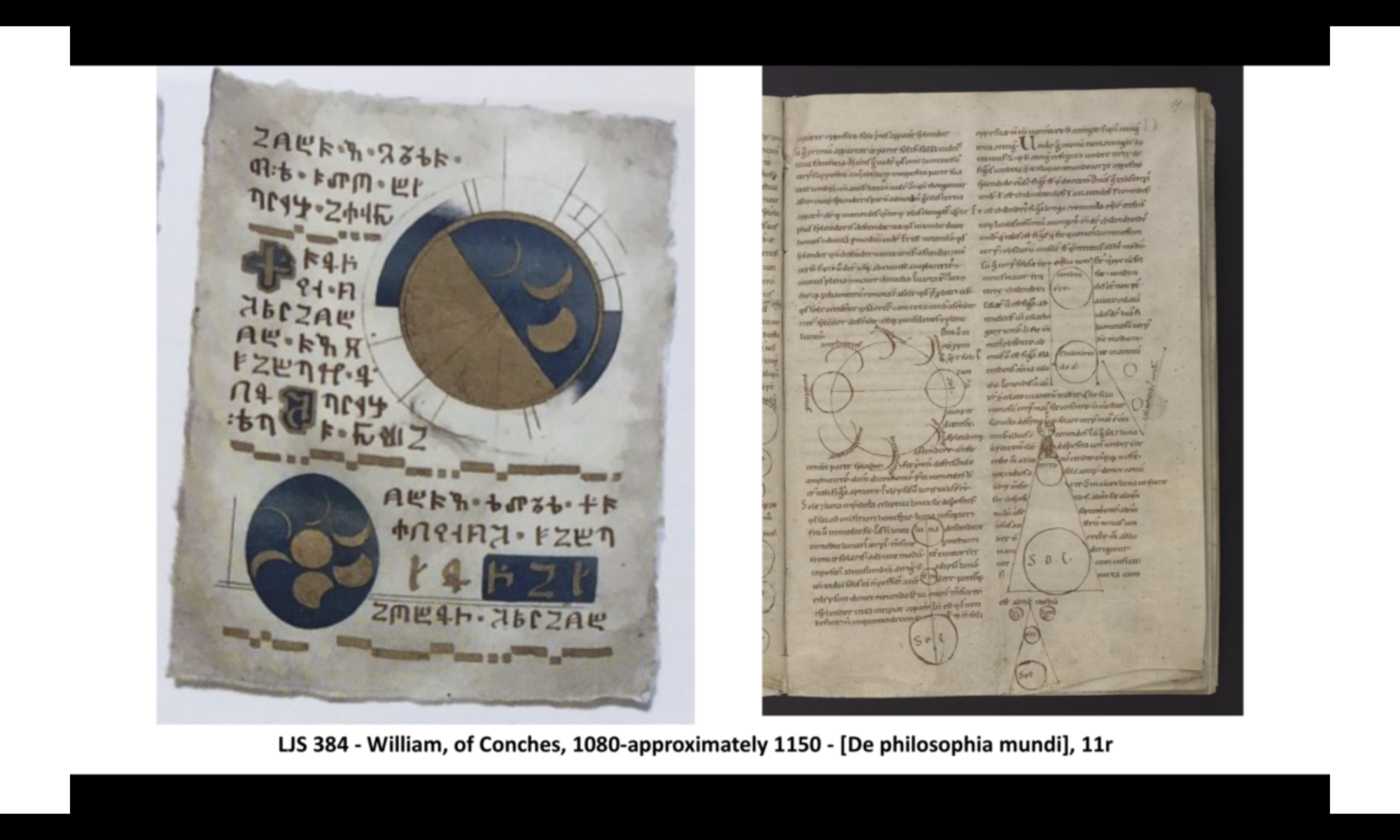

If you’re here because you read the Specific Knowledge post and you’d like to know more about the manuscripts in the figures, welcome! Below you’ll find full citations, links to the catalog records and digital facsimiles, and videos where they exist.

All the books featured in the post are from the collections of the Kislak Center for Special Collections, Rare Books and Manuscripts at the University of Pennsylvania Libraries.

Continue reading “Addendum: Full citations for Specific Knowledge post”Collection Sharing as a form of Digital Collections Security

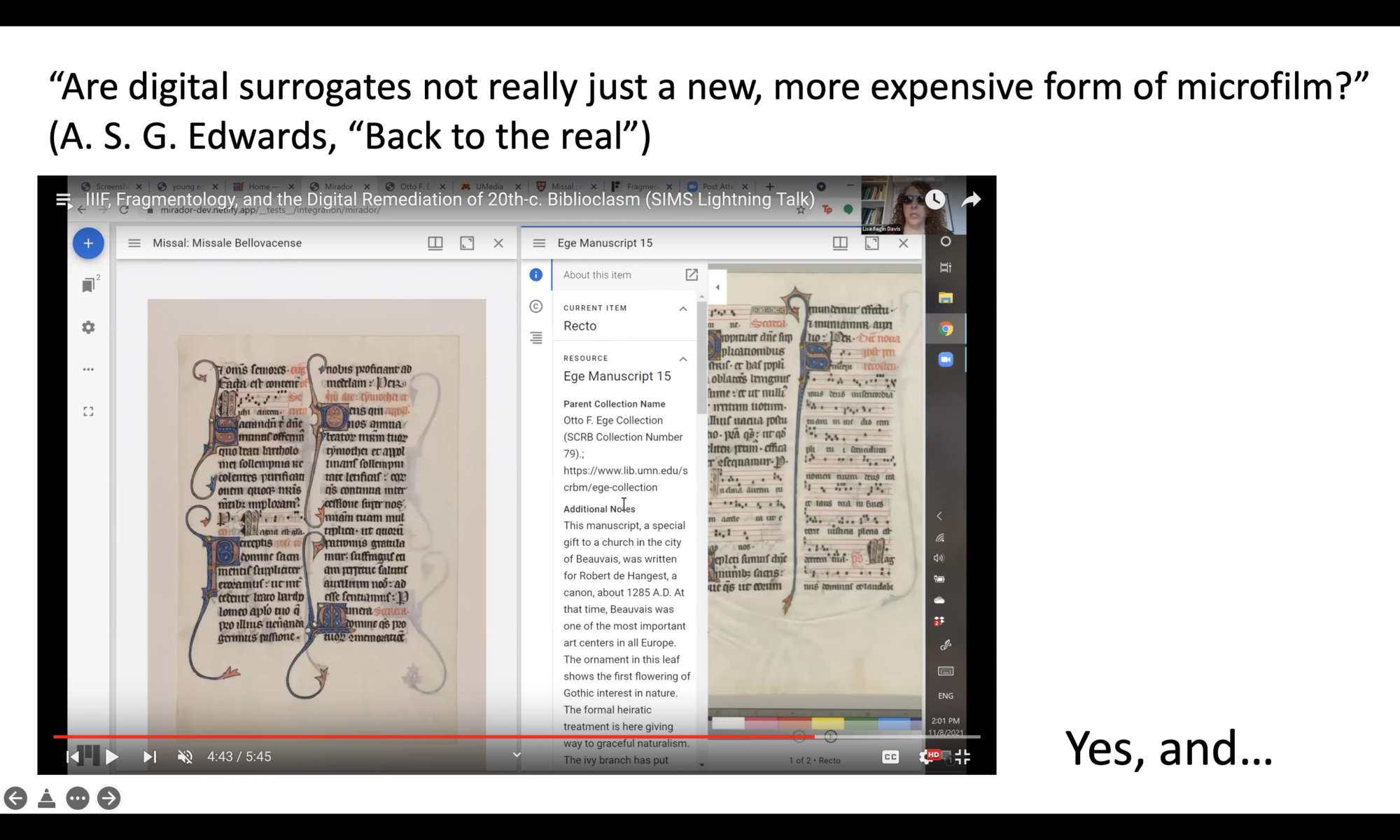

This blog post was originally conceived as a contribution to Now You See It Now You Don’t: Sustainable Access in a Digital Age, an event organized by the Bodleian Library and held on Zoom on February 7, 2024. Although my name appears in the list of contributors, I caught the flu that week and wasn’t able to attend. But I was prepared, and even though I’ve no doubt other people there said similar things, I wanted to post this for FOMO if for no other reason. This post consists of screenshots of my slides, and accompanying notes that explain my points further.

Continue reading “Collection Sharing as a form of Digital Collections Security”IMFM Episode 15: Jo Koster on prayer, manuscript digitization, and women’s literacy in the middle ages

Tumblr was borking so I am posting the show notes over here this week. Welcome to my blog!

Continue reading “IMFM Episode 15: Jo Koster on prayer, manuscript digitization, and women’s literacy in the middle ages”Manuscripts, Humanity, and AI

(a few words originally posted on Twitter on March 27, 2023)

I’ve been trying all morning to figure out what bothers me about these Mid journey-generated manuscripts without simply sounding like a Luddite, and I think I finally have it.

Continue reading “Manuscripts, Humanity, and AI”Modelling the Historical Manuscript: Theory and Practice

Presented in the session Materiality of Manuscripts III: The Codex at the International Medieval Congress, Leeds, UK July 5, 2022

Good morning, good afternoon. Thank you to Katarzyna and Kıvılcım for organizing these sessions on Materiality of Manuscripts for IMC 2022. I’m Dot Porter and I’m going to talk about modeling the historical manuscript theory and practice.

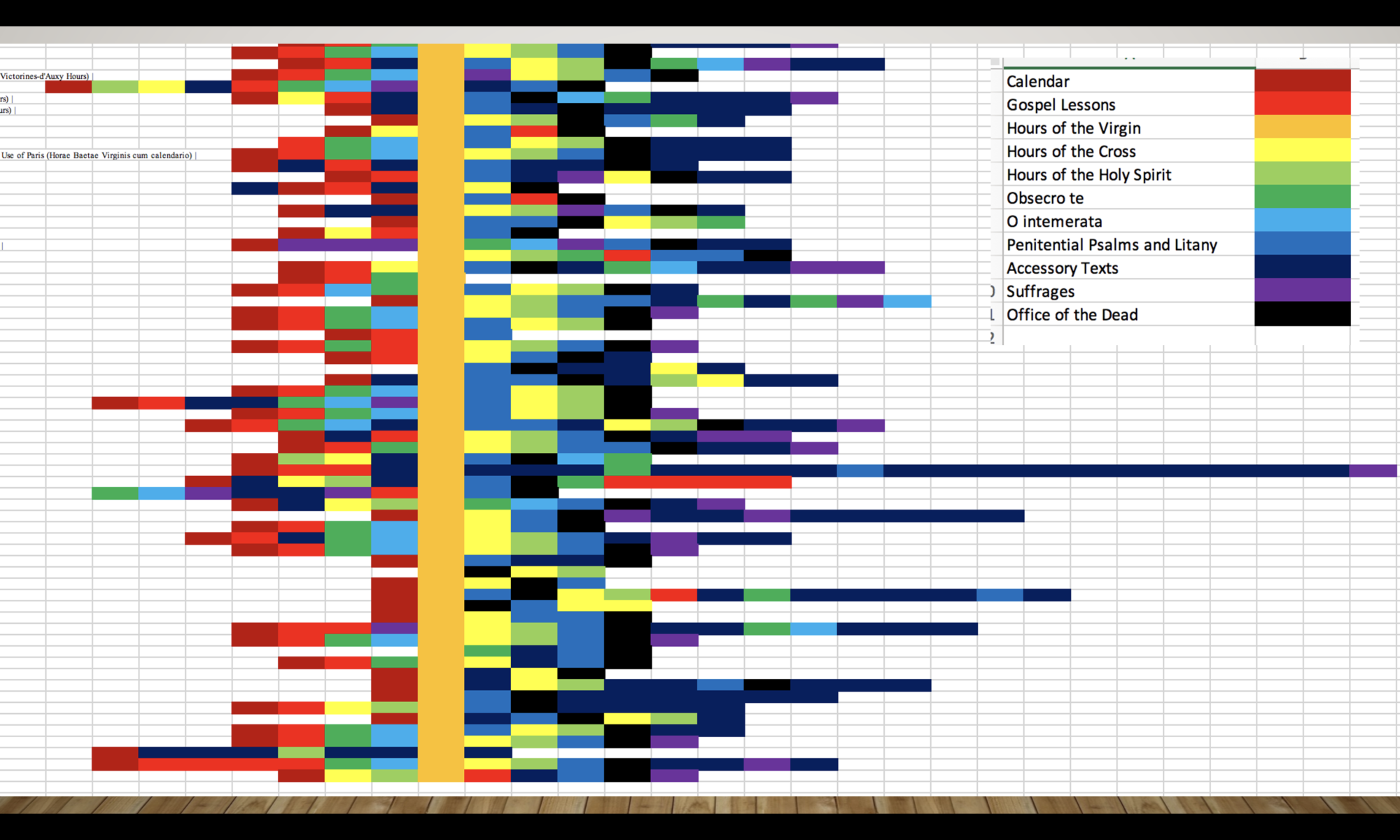

Continue reading “Modelling the Historical Manuscript: Theory and Practice “(More) Books of Hours as Transformative Works

Originally presented as the keynote lecture for Bindings Across Physical Formats and Digital Spaces, organized by the Center for the History of Print and Digital Culture, University of Wisconsin Madison, Madison, WI, June 2021. This is an expansion of the work described in my blog post Books of Hours as Transformative Works posted in November 2019.

Continue reading “(More) Books of Hours as Transformative Works”Aionomica, Rammahgon, and De sphaera mundi: Bibliographic Medievalism in Star Wars

Presented by Dr Brandon Hawk and Dot Porter at Books on Screen: A Virtual Symposium, University of Leeds and Anglia Ruskin University, November 3, 2021

Continue reading “Aionomica, Rammahgon, and De sphaera mundi: Bibliographic Medievalism in Star Wars”Manuscript Loss in Digital Contexts

Originally presented at the 14th Annual Schoenberg Symposium on Manuscript Studies in the Digital Age, November 17, 2021

Continue reading “Manuscript Loss in Digital Contexts”From Another Point of View: Exhibiting Manuscripts Online and in Person

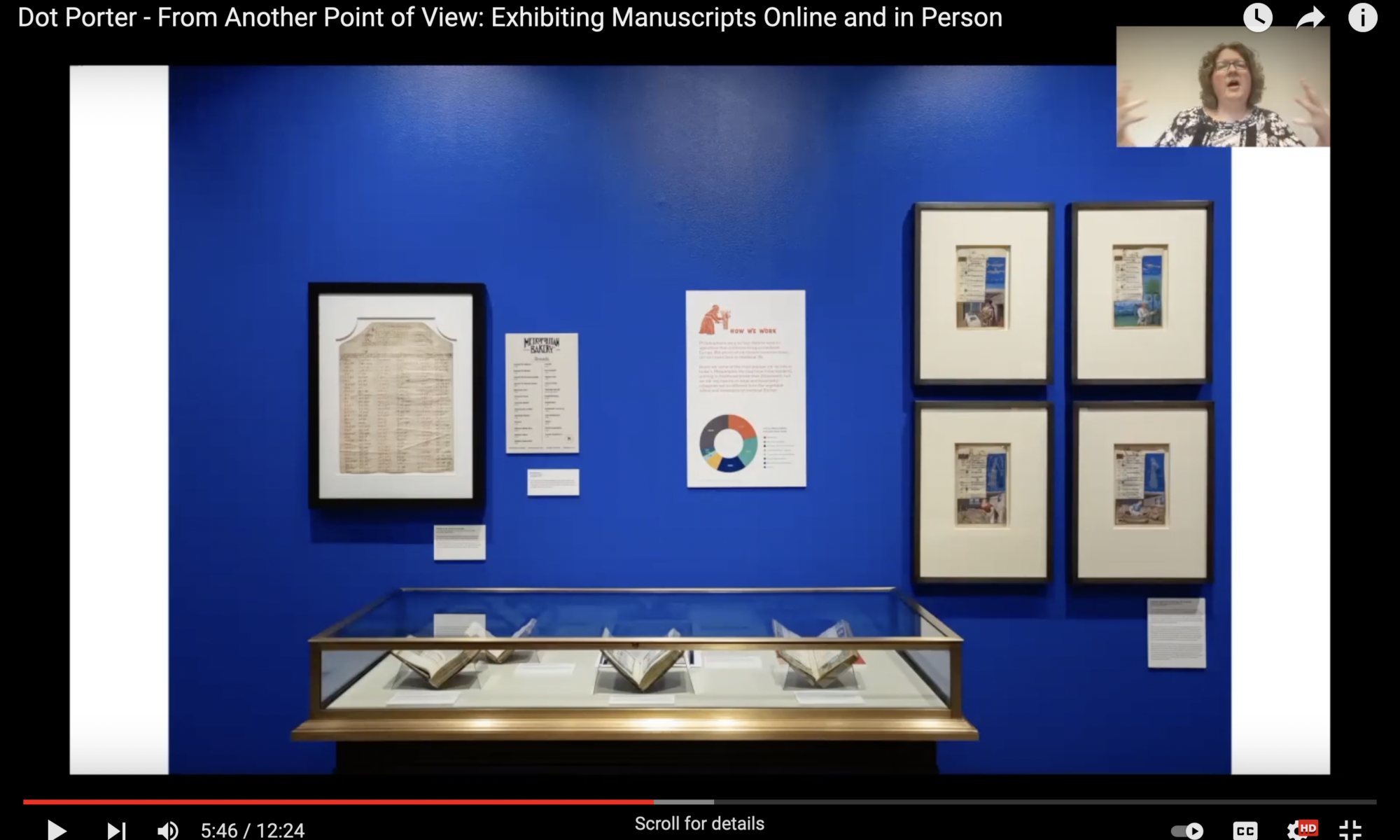

I recorded this brief presentation in September 2021, as part of “the digital medieval manuscript: an expert meeting,” organized by Kathryn Rudy at the University of Saint Andrews and held virtually on October 8, 2021.

Continue reading “From Another Point of View: Exhibiting Manuscripts Online and in Person”